Cosmology of the Quran

This article or section is being renovated. Lead = 4 / 4

Structure = 4 / 4

Content = 4 / 4

Language = 4 / 4

References = 4 / 4

|

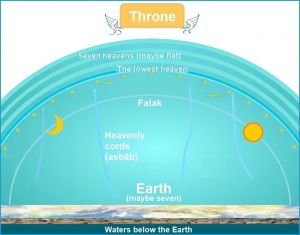

The Qur'anic universe comprises "the heavens and the earth, and all that is between them". Many verses expand on the various elements of this scheme, without going into great detail. Overall, a picture emerges of a flat earth (and perhaps seven of these), above which are seven heavenly firmaments of uncertain shape (commonly assumed to be domed; more recently some historians have argued that the Qur'anic heavens are flat) and held up without visible pillars. Lamps adorn the lowest of these heavens. The sun and moon circulate in them in a partly ambiguous manner. Allāh resides in heaven above the creation, sitting on a throne. Academic work has situated this picture within the context of earlier Mesopotamian and Biblical cosmological concepts, while noting its own distinctive identity.

Relatively few modern academic scholars have made dedicated attempts to piece together the cosmography of the Quran, in whole or in part. One of the most comprehensive such surveys has been conducted by Mohammad Ali Tabatabaʾi and Saida Mirsadri of Tehran University in 2016 (which can be read for free using a jstor.org monthly free article allowance).[1] They note that the new movement in the field commenced with Kevin van Bladel's work regarding individual elements of the picture in the context of the journeys of Dhu'l Qarnayn[2] and the heavenly cords (asbāb) by which he traversed the world, and which, for example, Pharaoh attempted to reach by building a tower[3].

By taking the Quranic descriptions in their own right and in the context of the more ancient cosmologies of Babylon and the Bible, but without appeal to later works of tafsir or hadith, which show the influence of Hellenistic (Greek) ideas acquired by the Muslims after the advent of Islam, Tabataba'i and Mirsadri argue that in various ways the Quranic cosmology has its own distinctive characteristics as well as inherited concepts, just as it interacts with the ideologies of its environment, taking some things and rejecting others. Their observations in particular are regularly cited in this article.

The Heavens (al-samāwāt) and the Earth (al-arḍ)

Any accounting of the cosmology of the Qur'an must begin with the fact that the Islamic universe is extremely simple. It consists entirely of three components: "the heavens and the earth, and all that is between them" (see for example Quran 50:38), the latter of which contains such things as clouds (Quran 2:164) and birds (Quran 24:41). More often, just the heavens and earth are shorthand for the entirety of creation.

There is no indication of any of the other features of the universe that modern peoples take for granted. There is no concept of solar systems, of galaxies, or of “space.” There is no hint that the earth is a planet like the other planets visible from it, or that stars are other suns, just very far away. Qur'anic cosmology is primarily limited to that which is visible to the naked eye, and where it goes beyond this, invariably strays from what has been learned by scientific investigation.

The fundamental status of the “heavens and the earth” as the two main components of creation is emphasized repeatedly in the Qur'an, and it is the “separation” of the two that stands as the initial creative act of Allah (this verse has an interesting parallel in Syriac Christian literature).

Additionally, the Qur'an is clear that when Allāh created the heavens and the earth, the earth came first.

And

The Earth and its waters

Tabataba'i and Mirsadri note that the Qur'an "takes for granted" the flatness of the earth, a common motif among the scientifically naive people at that time, while it has "not even one hint of a spherical earth"[4] Meanwhile, certain Christian scholars of the 6th century influenced by the ancient Greeks, in dispute with their counterparts in the east, believed in its sphericity, as noted by van Bladel.[5] Damien Janos in another paper on Qur'anic cosmography has similarly noted that while the exact shape of its boundaries are not described, "what is clear is that the Qurʾān and the early Muslim tradition do not uphold the conception of a spherical earth and a spherical universe. This was a view that later prevailed in the learned circles of Muslim society as a result of the infiltration of Ptolemaic astronomy".[6]

Repeatedly, the Qur'an uses various Arabic terms that convey a flat earth, spread out like a carpet. For a much more comprehensive compilation of verses, see Islamic Views on the Shape of the Earth.

In fact, at one point the Qur'an even emphasizes how much flatter the earth would be were it not for the mountains that disrupt the view.

As Tabataba'i and Mirsadri note[7], the mountains are heavy masses described as pegs to prevent the earth from shaking.

One unclear facet of Islamic cosmology is that the Qur'an likens the creation of the earth to the seven heavens:

Tabataba'i and Mirsadri observe that the plural for the earth (al ard) is never used in the Quran, though most Muslim commentators interpreted this verse to mean seven earths. Instead, they consider the verse to be likening the earth to the heavens in shape and extent (i.e. a flat expanse) as part of a broader argument in their paper that the Qur'an describes a set of seven flat, stacked heavens (see below).[8]

In the hadiths, the idea of seven earths, one above the other is already apparent.

(For a more comprehensive analysis of Islamic literature covering the the Seven Earths, see: Science and the Seven Earths).

Janos notes that Sumerian incantations dated to the 1st millenium BCE mention both the seven heavens and seven earths (citing Wayne Horowitz, who translated them as "the heavens are seven, the earths are seven").[9] Tabataba'i and Mirsadri similarly note from Horowitz that this tradition was popular in the near east in first millennia BCE and CE, though also that only the seven heavens, but not seven earths found their way into the Hebrew literature.[10]

While contrasting the Biblical view of fresh and salty waters with the two seas of certain Qur'anic verses (fresh and salty - see for example Quran 25:53 and the quest of Moses to find their junction in Quran 18:60), they note another difference to the Biblical and Mesopotamian cosmologies, which is that the Qur'an does not explicitly mention an ocean encircling the flat disk of the earth.[11]

The two seas are very much on the surface of the earth.

The seven Heavens and their denizens

The shape of the heavens

While many classical Muslim scholars, and modern academics (due to their interpretation of other ancient cosmologies) tend to assume that the Qur'anic heavens are domed, Tabataba'i and Mirsadri observe that there is no indication in the Qur'an that they touch the earth's boundaries. The sun and moon are placed in the heavens (Quran 71:16 and Quran 78:13), the lowest of which are adorned with lamps Quran 41:12. Janos discusses verses Quran 21:30 and Quran 36:40 in which the sun and moon (as well as night and day) move in a "falak" (an ambiguous term that may have meant a circuitous course/sphere/hemisphere - see Geocentrism and the Quran), but notes that this was not considered semantically identical with the samāwāt, or heavens, and they were not necessarily conceived as having the same shape.[13]

The following is a summary of the arguments Tabataba'i and Mirsadri employ to argue that the Qur'anic heavens are flat:[14]

- They interpret Quran 51:47 ("We have built the heaven with might, and We it is Who make the vast extent (thereof).") to mean that the heavens are continually expanded, which favours a flat expanse rather than a dome (it could be added in that case that the next verse about spreading the earth, with the same grammatical form, too fits this view). They also consider that verses mentioning invisible pillars (see below) favour a flat, roof like firmament.

- Verses in which the seven heavens are likened to the earth (their interpretation of Quran 67:12 mentioned above), including in terms of their width e.g. Quran 57:21 "a Garden whereof the breadth is as the breadth of the heavens and the earth".

- These heavens are arranged in layers (Quran 67:3, Quran 71:15), which more obviously suggests flatness, and this word tibiqan is similar to the Babylonian tubuqati, suggesting that seven superimposed flat heavens is a belief they have in common.

- While interest in the heavens (as opposed to their contents) is largely absent from pre-Islamic poetry, the poems of Umayya ibn Abī al‐Ṣalt (d. 5 / 626) likened the heavens to seven floors one above another, and the carpet shaped earth to the uplifted heaven ("And [he] shaped the earth as a carpet then he ordained it, [the area] under the firmament [are] just like those he uplifted").

- Despite the obvious potential use of tents as an analogy for the heavens, the Qur'an does not do so. Mountains act as pegs to stabilise the earth rather than hold down a heavenly tent canopy.

- The notion of a flat sky was common in ancient Mesopotamia and the near east (as also noted by Janos, citing Horowitz[15]) though some scholars instead say that the universal belief of the scientifically naive peoples of the world was that it was dome shaped. Those who suppose that the pre-Islamic Arabs had a dome shaped conception due to their tent dwellings ignore the evidence that Mecca was an urban environment with flat roofs.

- They argue that the Qur'an's ideological antipathy to the Bedouins would have extended to their use of tents for pagan practices, and for this reason may have rejected any possible existing analogies with the heavens.

They note that Janos too favours a flat heavens interpretation. For him, it was enough that the Qur'anic firmament is likened to a bināʾ (structure) or saqf (roof, though could also mean tent covers[16] Quran 2:22, Quran 21:32, Quran 40:64); To them, the etymology of saqf suggests that it originally referred to flat roofs, including in the Qur'an Quran 16:26, Quran 43:33); and arranged in layers as mentioned above - they agree with Janos on the strength of this latter point, though he is also open to the dome-shaped view based on tafsir sources rather than any internal evidence, while van Bladel relies mainly on pre-Qur'anic sources for his discussion of whether the Qur'anic heavens are a dome, tent or roof.[3]

Further evidence that they do not mention is found in Quran 21:104 and Quran 39:67, which state that the heavens will be rolled up/folded up come the day of judgement.

On the other hand, the moon, and probably the sun, are within the seven heavens according to Quran 71:15-16, which may lend support to the assumption shared by some of Muhammad's companions and various classical scholars that the heavens are domed, particularly as these celestial bodies, as well as the night and day, are said to float in a falak (see above). This verse is mentioned by Tabataba'i and Mirsadri without comment on the potential difficulty.[17] In van Bladel's analysis of the Qur'anic cosmography, the sky has gates[3], which perhaps offers a solution (in the Syriac Alexander legend, the sun passes through gates, but in order to travel beneath a dome rather than above a flat sky layer[2]).

A further difficulty they do not discuss is that the lowest of the Quranic heavens is adorned with stars/lamps (Quran 37:6 and Quran 41:12). Only the most casual observers would imagine the stars as adorning a flat surface. Stars rise and set through the night, appearing to revolve around Polaris (the "pole star"), 21 degrees above the Arabian horizon.

Solid firmaments held without visible pillars

Tabataba'i and Mirsadri notice that, as with other ancient cosmologies, the Qur'anic sky/heaven is a solid object.[18] Unlike with the heavenly pillars in the Bible, the Qur'anic heavens are raised without visible pillars[19] (Quran 13:2 and Quran 31:10; Ibn Kathir in his tafsir notes two views on what is a somewhat ambiguous phrasing, as though the author was hedging his bets: "'there are pillars, but you cannot see them,' according to Ibn `Abbas, Mujahid, Al-Hasan, Qatadah, and several other scholars. Iyas bin Mu`awiyah said, 'The heaven is like a dome over the earth, meaning, without pillars.'"[20]).

While Tabataba'i and Mirsadri take these to be invisible pillars, Julien Decharneux in his book on Quranic Cosmology reads these verses as denying that any form of pillars hold up the firmament, noting that other verses refer to Allāh holding the heavens (Quran 22:65 and Quran 35:41). He observes that this is in contrast to the Biblical view but in line with various Syriac Christian writings in the centuries leading up to Islam.[21]

Remzā (mentioned below) commonly refers to a 'sign, gesture or symbol' in Syriac, associated with divine powers.[23]

Tabataba'i and Mirsadri note that various verses describe the heavens as a structure or edifice with no fissures, though fragments of it may fall on the earth.

And the fact that the sky/heaven is solid is shown by the concept of pieces falling and potentially injuring residents of the earth.

These heavens are described as strong.

In fact, they are so substantial that it is even conceivable to climb up onto them using a ladder.

It is a guarded roof (presumably a reference to shooting stars chasing devils in other verses):

Quran 81:11 adds that the sky is like a covering that can be 'stripped away', while Quran 21:104 states that it will eventually be rolled or folded up like a parchment and Quran 39:67 says that the heavens will then be held in Allāh's hand. This will occur after it has been slit (furijat Quran 77:9), rent asunder with clouds (Quran 25:25), split (inshaqqat Quran 55:37, Quran 84:1, Quran 69:16 with angels appearing at its edges Quran 69:17). The heaven will become as gateways (Quran 78:19, a possibility also alluded to in Quran 15:13-15).

To further expound on the nature of the seven heavens, the hadith are helpful. Here we learn the distances between each heaven, as well as what is on the other side of the furthermost.

They said: Sahab.

He said: And muzn? They said: And muzn. He said: And anan? They said: And anan. AbuDawud said: I am not quite confident about the word anan. He asked: Do you know the distance between Heaven and Earth? They replied: We do not know. He then said: The distance between them is seventy-one, seventy-two, or seventy-three years. The heaven which is above it is at a similar distance (going on till he counted seven heavens). Above the seventh heaven there is a sea, the distance between whose surface and bottom is like that between one heaven and the next. Above that there are eight mountain goats the distance between whose hoofs and haunches is like the distance between one heaven and the next. Then Allah, the Blessed and the Exalted, is above that.Ignoring the giant mountain goats which are never mentioned in the Qur'an itself, the outermost heaven lies beneath a sea that is as deep as the distances between adjacent heavens. That Allāh’s “throne” is upon such waters is mentioned in the Qur'an as well as the hadith.

There are however no mentions of galaxies, quasars, galaxy clusters or empty space. Simply water, a throne, and Allāh himself.

Additional details concerning the individual heavens are found in the accounts of Muhammad’s “night journey.” Rather than quoting at length, readers are referred to Sahih Bukhari 9:93:608 for the long version. But here are the key points.

Each of the seven heavens is populated by multiple angels and a few other folks as well. These heavens are entered through doors in the solid domes, each with an angelic guard and each populated by a resident prophet. For example, immediately above the dome of the first heaven is where Muhammad met Adam, and discovered (in the absence of true geographic knowledge) the sources of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (the idea that the rivers of paradise are connected to Earth is also found in Sahih Bukhari 4:54:429 and Sahih Muslim 40:6807, also likely potentially to the word 'sarab' in Quran 18:61).[25] The second heaven is the home of the Prophet Idris. Aaron is in the fourth heaven, Abraham the sixth, and Moses the seventh.

The scale (al-mīzān)

And the stars and trees prostrate.

And the heaven He raised and imposed the balance

That you not transgress within the balance.

And establish weight in justice and do not make deficient the balance.

A mysterious verse occurs in the 55th surah, al-Rahman. In an opening passage entirely about the signs to be seen in the creation of the heavens and earth, verse 7 says "And the heaven He raised and imposed the balance". The word translated "balance" in verse 7 is al-mīzān, used elsewhere to mean scales of justice. Academic scholars generally believe the next two verses digressing about justice in terms of literal scales were placed there by a confused editor when the Quran was compiled. As so often with 21st century academic scholarship of the Quran, the meaning has become clearer by comparing with contemporary Syriac literature. Julien Decharneux has identified a precedent in two 6th century CE writers, Narsai and Jacob of Sarugh, two of the Syriac Christian authors whose writings are often paralleled in the Quran:

Thus it seems that here the Quran is referring to a firmament that fairly divided the waters above and below it.

The gates of the heavens

As Nicolai Sinai notes,[28] this is further supported by the sky (al-samā) having gates, a common cosmological idea in antiquity[29] (see: Quran 7:40, Quran 15:14, Quran 78:19, Quran 5:11 of which Allāh holds the keys Quran 42:12). Their opening causes the water to fall and drown the people of Noah once he is safe in the boat (Quran 54:11-12; cf. Genesis 7:11 and 8:2[30]), which would seem to presuppose the Biblical notion that the firmament separates the waters above.

The sky is also the source of vivifying precipitation[31] (e.g., Quran 2:22, Quran 30:24, Quran 43:11, Quran 45:5, Quran 50:9, Quran 71:11 and Quran 41:39), with its life giving qualities to 'dead' soil shown as proof of God's ability to resurrect the dead (e.g. Q 43:11 '“and Who sent down out of heaven water in measure; and We revived thereby a land that was dead; even so you shall be brought forth”). This is in line with the contemporary view of the qualities of the celestial waters, that are consistent with the fish miraculously regaining life in Q 18:61 and 63, and meaningfully takes place where the heavenly ocean joins the lower part of the world,[32] which Angelika Neuwirth notes is the exegetical view most in line with the Qur'anic evidence.[33]

And deluge from below

As Wheeler and Noegel (2010) note,[34] Muslim traditions embrace the concept of a three-tiered universe: the heavens above, earth in the middle, and hell below, often depicted as an underground, fiery, or watery realm. Alongside Islamic traditions which place it here, they note Qur'anic evidence in that it describes hell as being filled with boiling water beneath the Earth (e.g. see: Quran 56:42-44, Quran 55:43-44, and Quran 22:19-22).

When flooding the Earth in the Qur'anic story of Noah and the Ark, along with the (presumably normal) water falling from the gates above in the sky just mentioned, the great flood is also described as originating from beneath the earth, stating the waters overflow from an 'oven' in contrast with those above. This water also comes via springs bursting through the Earth, suggesting a connection between them to hell or at least the lower world.

The Arabic verb most commonly translated as "gushed forth" (fāra فَارَ) in the following two verses means "overflowed", or "boiled" in the context of water in a cooking pot,[35] as well as in the other verse where the same root is used as a verb Quran 67:7. The possible meaning of the oven "boiling" water from the Earth to flood it in the following verses has been interpreted by some scholars as a metaphor for hell, as Wheeler and Noegel (2010) note it is also described as a 'pit' in which there are fires (e.g. Quran 101:9-11).[36] Other evidence not mentioned by them includes the warm muddy spring the sun sets in at night and possibly comes out of on the other side of the world.

More recent scholarship, however, particularly by Olivier Mongellaz in 2024,[37] has identified that these verses very likely reflect a late antique legend in which water gushing up through a bread oven (a large hole dug into the ground) was a sign warning Noah's family of the imminent flood (see Parallels Between the Qur'an and Late Antique Judeo-Christian Literature).

The Sky-ways (asbāb) of the Heavens

Traditional Islamic scholarship[38] has recognised that the sky/heavens (al-samā) are equipped with what appear to be pathways or conduits, aptly named sky-ways by Tomaso Tesei,[39] called sabab (singular) asbāb (plural) in classical Arabic and in the Qur'an. These are some kind of ropes or cords (as per their literal meaning)[40] that support or run along the high edifice of heaven and which can be traversed physically by people who arrive at them. In effect, asbāb in the Quran are "heavenly ways" or "heavenly courses" that humans might attempt to traverse to gain access to the highest reaches of heaven, but that God alone controls[41] leaving only chosen righteous individuals to ascend, like many ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern traditions, including pre-Islamic Arabic poetry using the same term.[42] Tradition has recognised them in Q40:36-37 and Q38:10.[43] In verses Q40:36-37, Pharaoh asks Haman to build a tower to reach the heavens (asbāb) to see the deity of Moses, but is blocked by Allāh, while Q38:10 questions whether the heavens and the earth belong to anyone other than God and challenges others to ascend by these ways.

Al-Rabīʿ ibn Anas (d. 756), to whom is attributed an early Quran commentary on verse Q38:10: "The asbāb are finer than hair and stronger than iron; it [sic] is in every place although it is invisible.[44]

For other uses of 'sabab' elsewhere in the Quran, divergent views are often given by exegetes, including its literal meaning of a rope one ascends/descends by,[45] and separately a generic ' way' or 'road', which often results in the stretching the meaning of other words in the verses, regarding which a further discussion of the forced meanings can be read for free in Kevin van Bladel's full 2007 article "Heavenly cords and prophetic authority in the Qur’an and its Late Antique context", on pages 229-230.

Van Bladel (2007) and Sinai (2023)[46] note that the term has a specific and consistent meaning of sky-ways (rather than a normal 'way', 'pathway' or 'road' as is often translated), with most cases referring to Allāh blocking those trying to ascend them. However, in one story, Dhu'l-Qarnayn in Quran 18:84, Quran 18:85, Quran 18:89 and Quran 18:92 is given these sky-ways/cords by Allāh to travel across the Earth to where the sun sets, then to where it rises, and to another far off land (much like the Syriac Alexander Legend from which the story ultimately is derived).[47] This suggests that these cords (asbāb) also stretch across the sky. This interpretation is supported in some early Islamic scholars such as al-Ṭabarī (d. 923 AD) in his Qur'anic commentary, and Ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥakam (d. 871 AD) in his Kitāb Futuḥ Misr, who have Dhul-Qarnayn being brought up them (took him up 'araja bihi) by an angel.[48]

The places of ascent (al-maʿāriji)

Also mentioned are the (l-maʿāriji ٱلْمَعَارِجِ) meaning 'A ladder, or series of steps or stairs, a thing resembling a ladder or stairway, or places of ascent'[49] where angels can ascend, as taken by many traditional and modern commentators.[50]

Angelika Neuwirth notes on this cosmological function ".. imposed by God, the “Lord of the ladders.” If one understands this predication, which occurs only once in the Qur’an, in agreement with the threatening context (verses 5–7), then one would have to think of maʿārij as the ladders knotted from fraying ropes in the Christian image tradition, across which those awakened from death go over the abyss into heaven, so that only the good are safe from falling into the abyss—a conception which is also reflected in the traditional Islamic ṣirāṭ image of a rope ladder stretched across an abyss, which occurs in later literature."[51]

Sinai et al. (2024) note that the word maʿārij, which corresponds to Ethiopian maʿāreg (cf. Ethiopian ʿarga , yeʿrag , “to climb up”), which in the Ethiopian Bible translation refers to the ladder to heaven that Jacob sees in Genesis 28:10, is otherwise only used once elsewhere in Quran 43:33 as a profane (non-religious/normal) staircase in a house, implying this is meant to be a tangible object.[52]

The seven paths/ways (ṭarāiqa)

We are told there are seven paths/ways/courses ṭarāiqa[53] above (fawqa)[54] us.

Usually taken by exegetes to be a reference to the seven heavens, as they are paths for the angels, or the seven paths of the visible celestial objects moving that can be seen without a telescope known to the Arabs (the sun, moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn).[55] Modern academics on the Corpus Coranicum project note it most likely means heavens, but may also be the asbāb / sky-ways, mentioning: Ṭarāʾiq etymologically evokes the idea of (walkable) paths and thus possible ways of accessing the divine presence.[56]

The stars, the sun, and the moon

The stars are inside the closest heaven, as the Qur'an is quite explicit on this point.

The sun and moon are a bit more ambiguous, as all we know is that they are in the heavens, and not explicitly inside the lowest of them. A possible interpretation of "in them" (fīhinna) here could be that the sun and moon are just underneath the lowest heaven i.e. "in them" in the sense that the heavenly domes surround them.

These two lights, as well as the night and day float in a circuitous course/sphere/hemisphere (a falak).

And at the end of their daily paths across the sky, the sun (and presumably also the moon and stars) pass through the earth’s flat surface near the far Western edge using openings filled with water.

Once out of view of the humans that populate the top of the earthly disc, their motion stops, and they rest for the night in particular resting places.

At some point during the night, however (and here again turning to the hadith for details) the sun must negotiate its return the next day with a direct appeal for Allāh’s permission.

The hadith also occurs in Sahih Bukhari 4:54:421 (note that Khan inaccurately translates maghribiki here as "the west" instead of "your setting place") where it is presented as the interpretation of Quran 36:38 quoted above.

With permission to rise received, the sun passes back through the flat earth near its Eastern edge to commence the next day. While no “muddy pools” are specifically mentioned for the sunrise, the description of people living nearby the exit point mirrors the description of the place where the sun set.

Solar and lunar eclipses

The Qur'an demonstrates no understanding whatsoever of eclipses. Perhaps this is understandable. The hadith claim that Muhammad only experienced one solar eclipse during his lifetime, an experience which frightened him into a spectacular act of piety. But the Qur'an only makes a single reference to eclipses, and that is a lunar eclipse that will take place at the end of the world.

In fact, the Qur'an actually makes a statement that would conceivably make eclipses impossible.

For a solar eclipse to occur however, the sun and the moon actually must (from the perspective of the earth) "catch up" to each other in their "orbits." But since the moon itself is not visible at that time, the authors of the Qur'an never noticed this.

But then, when discussing the end of time the Qur'an assumes that a lunar eclipse (which can only occur when the sun and moon are on opposite sides of the earth) can occur at the same time that the sun and moon finally do “catch up” to each other.

But when sight is confounded

And the moon is eclipsed

And sun and moon are united,

The “uniting” of the sun and the moon not only demonstrates a singular instance when they do “catch up” with each other, but suggests that its author assumed the common perception that the sun and moon are of comparable size and distance.

The stars, planets, and meteors

It is not obvious from the translations of the Qur'an that the authors of the Qur'an actually distinguished between stars and planets, as the same word is often translated to mean either. But as ancient peoples generally knew that planets were different from ordinary stars (they moved) it is a safe assumption that the earliest Muslims were equally aware.

But the mistaken (if understandable) belief that stars are very small nearby objects is not merely reflected in the placement of them inside the nearest heaven. As with most other ancient people, the authors of the Qur'an believed that meteors literally were “falling stars” (see: Shooting Stars in the Quran). Verse 67:5 tells us they are weapons against devils and jinn.

This appears to be part of the protective role of the heavens.

See also Quran 15:16-18 and Quran 72:8-9.

Towers

The term used in 15:16 is burūjan, which is commonly translated, and has been understood by most to mean 'constellations/zodiac signs' or 'great stars'. However the word can also mean 'towers', and some classical commentators have suggested this meaning (along with mansions or castles),[57] and some modern Muslim translators have used this interpretation.[58]

Islamic scholars Gabriel Said Reynolds[59] and Julien Decharneux[60]support this interpretation of towers on the firmament, with the idea of the skies/heavens (samā) being a protected celestial fortress in both the Quran itself (e.g. Quran 41:12, Quran 21:32) and biblically related traditions.

The throne ('arsh) of Allāh

Tabataba'i and Mirsadri note that Allāh seems to reside in the Qur'anic heaven/sky, while his footstool (kursi) extends over the heavens and earth and his throne (arshi) is carried by angels (Quran 39:75 and Quran 40:7). This is very much similar to the Judeo-Christian view.[61]

As mentioned this throne sits on the cosmic waters in Quran 11:7, as similarly described in an apocryphal and pseudo epigraphical work known as 'the Cave of treasures'',[62] believed by many scholars to date to the early 7th century by a West-Syrian writer, who lived in the Sasanian-controlled part of Northern Mesopotamia hundreds of miles north of the Hijaz, who took many ideas from earlier Judeo-Christian works.[63]

Seats for the exhalted assembly

The Qur'an mentions sitting positions (maqāʿida)[64]the jinn used to sit in before being struck by stars/meteors. Crone (2017) notes, this is based off many previous religious traditions, including Judeo-Christian literature, where a divine council (called the 'exhalated assembly' in Quran 37:8) would gather around God's throne ('arsh) for special meetings, an idea itself based off earlier Earthly monarchies where kings would hold councils of their special advisors.[65]

Note in most translations maqāʿida is translated simply as 'positions'; however it refers to sitting places specifically,[66] (can be translated as seats such as by Arberry above) as one can see viewing how else the root is used in the Qur'an and classical Arabic dictionaries[67] rather than generic positions they happen to sit in, and the neutral term for hearing (lilssamʿi) is usually turned to the word 'eavesdropping'. Penchansky (2021)[68] notes the translators impose these meanings on the text due to later Islamic exegetes not being comfortable with the jinn accessing the divine presence, reflected in later tafsirs, so the idea that there were specific designated places made for the jinn became taboo, and the neutral term for listening/hearing (lilssamʿi) becomes translated as the negatively charged term 'eavesdropping'.[69]

The locations of Heaven (jannah) and Hell (jahannam)

Tabataba'i and Mirsadri observe that for the Qur'an, there is almost no reference to what is beneath the earth, except as no more than a geographic location. There is no explicit concept of an underworld, unlike Mesopotamian mythologies, as well as those of Egypt and Greece.[70] Tabataba'i and Mirsadri (2016) also note that while there is no explicit mention of an underworld, there is one mention to 'underneath the soil/ground, which "the waters stored there are to supply the wells and fountains and the water needed for the vegetation (Kor 39,21)," and note that other qur'anic references imply or state this is where the waters of the rain are stored (Quran 23:18 Quran 13:17 Quran 39:21).[71]

The Qur'an repeatedly described Jannah (Paradise) as comprising "Gardens from beneath which the rivers flow". Though not reflected in English translations, in every instance the definite article 'al' is used i.e. "the rivers". This is also noted by Tommaso Tesei, who has detailed how "sources confirm that during late antiquity it was widely held that paradise was a physical place situated on the other side of the ocean encircling the Earth. In accordance with this concept, it was generally assumed that the rivers flowing from paradise passed under this ocean to reach the inhabited part of the world." A notion of four rivers following a subterranean course from paradise into the inhabited world also occurs in contemporary near eastern and Syriac sources.[72]

Though again not reflected in many English translations, the rivers are also always described as running below/underneath (taḥt / تحت) paradise and the people in paradise (e.g. Quran verses 3:15, 3:136, 3:195, 3:198, 4:13, 4:57, 4:112, 5:12, 5:18, 7:43, 25:10, 47:12, 98:8) rather than simply 'in' (fee /في) paradise, giving weight to this interpretation.

The concept also appears in numerous sahih hadiths about Muhammad's night journey which mention the Nile and Euphrates, for example:

I was raised to the Lote Tree and saw four rivers, two of which were coming out and two going in. Those which were coming out were the Nile and the Euphrates, and those which were going in were two rivers in paradise. Then I was given three bowls, one containing milk, and another containing honey, and a third containing wine. I took the bowl containing milk and drank it. It was said to me, "You and your followers will be on the right path (of Islam)."

Later Islamic cosmology takes a perfectly prosaic position in terms of Paradise and Hell, and places them firmly within the cosmos that consists of the heavens and the earth. This is discussed with many narrations in an article on the Islamqa.info website.[73] The description of Muhammad’s “night journey” shows each of the seven heavens already populated with the departed prophets in Paradise. This is consistent with the Qur'anic description of the size of Paradise.

If the heavens (to include the seventh and largest) are already populated with denizens of Paradise, the width of Paradise would be precisely that of heaven and earth.

And since Paradise is on the other side of the first heaven, it might seem reasonable that Hell is at the level of the lowest earth, as appears in hadith. This is consistent with Qur'anic descriptions of hell as being a completely enclosed place.

And that humans who do not believe or are not righteous are told they will be put in the 'lowest of low' (which many classical tafsirs have stated means hell,[74] among other interpretations).

But We will reduce them to the lowest of the low,

except those who believe and do good—they will have a never-ending reward.The direction of hell on the day of judgement or from the perspective of those in paradise at least, when it is mentioned, is invariably “down.”

And in yet another reference, an observer is directed to “look down” in order to witness a denizen of hell.

Quran 7:46 mentions a partition (ḥijāb) separating paradise and hell, and Quran 57:13 describes a "wall with a gate" that separates believers from hypocrites, implying that paradise is enclosed and sinners are kept outside. The heights of this partition are occupied by men, likely angelic guards, who also call out to both the residents of paradise and hell.[75] Along with them calling out to each other Quran 7:44 and Quran 7:50.

As Sinai 2023 notes, reconciling this walled, guarded image of paradise with other passages that depict it as an elevated garden on a mountaintop is challenging, however, variations in the imagery of paradise are also present in other traditions, such as Syriac Christian literature.[76]

And so, we have the Islamic Universe in completion.

See also

- Islamic Views on the Shape of the Earth

- Geocentrism and the Quran

- Scientific Errors in the Quran

- The Islamic Whale

- Cosmology

External links

- Part 35: Seven Heavens and Seven Earths - YouTube Video

References

- ↑ Tabatabaʾi, Mohammad A.; Mirsadri, Saida, "The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself", Arabica 63 (3/4): 201-234, 2016, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24811784 also available on academia.edu

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Van Bladel, Kevin, “The Alexander legend in the Qur‘an 18:83-102″, In The Qur’ān in Its Historical Context, Ed. Gabriel Said Reynolds, New York: Routledge, 2007

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 van Bladel, Kevin, "Heavenly cords and prophetic authority in the Qur’an and its Late Antique context", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 70 (2): 223-246, 2007, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40379198

- ↑ Mohammad Ali Tabatabaʾi and Saida Mirsadri, The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself p. 211

- ↑ Van Bladel, Kevin, Heavenly cords and prophetic authority in the Qur’an and its Late Antique context pp. 224-226

- ↑ Janos, Damien, "Qurʾānic cosmography in its historical perspective: some notes on the formation of a religious wordview", Religion 42 (2): 215-231, 2012 See pp. 217-218

- ↑ Tabataba'i and Mirsadri, The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself p. 211

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 211 and 221

- ↑ Janos, Qurʾānic cosmography in its historical perspective p. 221

- ↑ Tabataba'i and Mirsadri, The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself p. 209

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 213-214

- ↑ Tabataba'i and Mirsadri, The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself pp. 217

- ↑ Janos, Qurʾānic cosmography in its historical perspective pp. 223-229

- ↑ Tabataba'i and Mirsadri, The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself pp. 218-234

- ↑ Janos, Qurʾānic cosmography in its historical perspective pp. 216-217

- ↑ saqf سقف - Lane's Lexicon p. 1383

- ↑ Tabataba'i and Mirsadri, The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself pp. 215

- ↑ Ibid. p. 209

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 216 and 220

- ↑ (English) Tafsir of Ibn Kathir for verse 13:2

(Arabic) Tafsir of Ibn Kathir for verse 13:2 - ↑ Julien Decharneux (2023), Creation and Contemplation: The Cosmology of the Qur’ān and Its Late Antique Background, Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 144-148

- ↑ Ibid. p. 146

- ↑ Ibid. pp 210-211

- ↑ Ibid. p. 146

- ↑ Tesei, Tommaso. Some Cosmological Notions from Late Antiquity in Q 18:60–65: The Quran in Light of Its Cultural Context. Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 135, no. 1, American Oriental Society, 2015, pp. 19–32, https://doi.org/10.7817/jameroriesoci.135.1.19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7817/jameroriesoci.135.1.19

- ↑ Julien Decharneux (2023), Creation and Contemplation: The Cosmology of the Qur’ān and Its Late Antique Background, Berlin: De Gruyter, p. 208

- ↑ Ibid. p. 209

- ↑ Samāʾ | heaven, sky Sinai, Nicolai. Key Terms of the Qur'an: A Critical Dictionary (p. 412). Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Anthony, Sean W., Dr.. Muhammad and the Empires of Faith: The Making of the Prophet of Islam. University of California Press. Kindle Edition. Location 1134 - 1145. The cosmological notion of humankind being blocked from accessing Paradise by gates and, thus, the existence of a heavenly gatekeeper is quite an ancient one and by no means exclusive to Jewish, Christian, or Muslim sacred cosmology. Indeed, where “the keys to heaven” as opposed to “the keys of Paradise” motif appears first in the Islamic tradition is in the Qurʾan itself.

- ↑ Genesis 7:11-8:2. New American Bible (Revised Edition) (NABRE). BibleGateway.com.

- ↑ Samāʾ | heaven, sky entry. Sinai, Nicolai. Key Terms of the Qur'an: A Critical Dictionary (p. 412). Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Tesei, Tommaso. Some Cosmological Notions from Late Antiquity in Q 18:60–65: The Quran in Light of Its Cultural Context. Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 135, no. 1, American Oriental Society, 2015, pp. 19–32, (pp. 28-29) https://doi.org/10.7817/jameroriesoci.135.1.19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7817/jameroriesoci.135.1.19

- ↑ Cosmology Entry. Space in cosmological context. Encyclopaedia Of The Qur’an. pp. 445-446. Angelika Neuwirth. 2001. Read online for free here: Encyclopaedia Of The Qur’an ( 6 Volumes). Page 15/325 / 482 of 3956 of PDF

- ↑ Scott Noegel and Brannon Wheeler (eds.), The A to Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism, Scarecrow Press, 2010, pp. 66-68 under a section titled "Cosmology and Cosmogony": "..The Bible and the Quran share some cosmological and cosmogonic views rooted in ancient Near Eastern conceptions of the world, such as the notion of a male creator God and his battle against the watery forces of Chaos, the division of the world into lower and upper realms in which the upper realm holds sway over the lower, and a teleological view of time with a definite beginning and end with which historical existence is contrasted. In terms of the structure of the world, Jewish and Muslim texts basically hold to the concept of a three-storied universe. The bottom level is often described as hell or the chthonic realm that is beneath the earth. In the biblical tradition, the Earth is conceived of as floating on a vast body of water. Exod 20:4, for example, delineates the heavens above, the earth below, and the water underneath the earth. The Quran depicts hell as consisting of liquid or boiling water with the earth spread out on top of it (Q 22:19-22, 55:43-44, 56:42-44). Hell also is described as a pit in which are the fires beneath the earth (Q 101:9-11). The great deluge is described as gushing forth from the earth (Q 54:12) and underground fountains (Gen 6:l1), perhaps reflecting an older cosmic battle myth in which water is personified as the monster of chaos that a god or hero conquers in creating and ordering the world. Much like the classical Greek conception, the earth or the middle realm of the cosmos is envisioned as a flat disc surrounded by the world ocean on all sides. The Quran describes the earth as flat and spread out (Q 71:19), wide and expansive (Q 29:56). There are points on the earth that serve as conduits or points of contact with the lower realms (pits, caves, water sources) and the upper realms (mountains, trees, high buildings)..."

- ↑ root fā wāw rā (ف و ر) Lanes Lexicon: fāra فَارَ Lane's Lexicon Dictionary p2456 & p2457

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Olivier Mongellaz (2024) Le four de Noé : un cas d’intertextualité coranique, Arabica 71(4-5), 513-637. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700585-20246900

- ↑ van Bladel, Kevin, "Heavenly cords and prophetic authority in the Qur’an and its Late Antique context", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 70 (2): 223-246, 2007. pp. 229 https://www.jstor.org/stable/40379198

- ↑ Tesei, Tommaso. 2014. “The Prophecy of Ḏū-l-Qarnayn (Q 18:83–102) and the Origins of the Qurʾānic Corpus.” In Miscellanea Arabica 2013–2014, edited by Angelo Arioli, 273–290. Rome: Aracne. As referenced in footnote 280. Sinai, Nicolai. Key Terms of the Qur'an: A Critical Dictionary (p. 411-412). Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Sinai, Nicolai. Key Terms of the Qur'an: A Critical Dictionary (p. 411-412). Princeton University Press.

- ↑ van Bladel, Kevin, "Heavenly cords and prophetic authority in the Qur’an and its Late Antique context", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 70 (2): 223-246, 2007. pp. 226 https://www.jstor.org/stable/40379198

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 231-232

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 229

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 237

- ↑ Sa Ba Ba سبب - Lane's Lexicon Book 1 Page 1285

- ↑ Sinai, Nicolai. Key Terms of the Qur'an: A Critical Dictionary (p. 411-412). Princeton University Press. The sky is equipped with what appear to be pathways or conduits, called asbāb (singular: sabab), that lead up to the top of the cosmic dome and which Pharaoh vainly aspires to ascend in order to look upon God (Q 40:36–37; cf. 38:10 and 22:15; see van Bladel 2007, 228–230).80 These heavenly pathways, aptly glossed as “sky-ways” (Tesei 2014, 280), would also seem to be intended in Q 18:84.85.89.92, which recount the travels of Dhū l-Qarnayn via different sababs that facilitate his extraordinary displacement from the place where the sun sets (Q 18:86) to the place where it rises (Q 18:90) to yet another place at the far edge of the civilised world (Q 18:93).81 Assuming that the word sabab carries the same significance in Surah 18, on the one hand, and in Q 38:10 and 40:36–37, on the other, the heavenly pathways would seem to run not only vertically upwards to the top of the heavenly dome but also to connect distant locations on the periphery of the earth, perhaps resembling cross beams traversing the lower reaches of the heavenly dome. The literal meaning of sabab, of course, is “rope” or “cord,” and the underlying idea may be that the sky is a tent, with vertical and transverse ropes forming part of its “girding or structure” (van Bladel 2007, 234–235). Though there is plainly some tension between picturing the sky as a solid edifice and as a tent, it is quite conceivable that the Qur’an attests to different manners of imagining the heavenly dome that were current in its cultural milieu. That the idea of heavenly asbāb had a wider circulation in the Qur’anic environment is, in any case, demonstrated by two verses of early Arabic poetry that van Bladel cites from a poem by al-Aʿshā Maymūn and from the Muʿallaqah of Zuhayr, both of which make reference, in parallel phraseology, to ascending “the asbāb of heaven (asbāb al-samāʾ) with a ladder (bi-sullam)” (Ḥusayn 1983, no. 15:32, and DSAAP, Zuhayr, no. 16:54; see van Bladel 2007, 231–232).82

- ↑ van Bladel, Kevin, "Heavenly cords and prophetic authority in the Qur’an and its Late Antique context", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 70 (2): 223-246, 2007. pp. 227 https://www.jstor.org/stable/40379198

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 227-228

- ↑ Lane's Lexicon Root: عرج مِعْرَاجٌ l-maʿāriji - Lane's Lexicon p1997

- ↑ See: e.g. commentaries on verse 70:3

- ↑ Neuwirth, Angelika. The Qur'an and Late Antiquity: A Shared Heritage (Oxford Studies in Late Antiquity) (Kindle Edition: pp. 186). Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Corpus Coranicum Sura 70 — al-Maʿāriǧ — “The Ladder to Heaven” Translated and analyzed by Nicolai Sinai. Chronological-literary commentary on the Koran, edited by the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences by Nicolai Sinai with the collaboration of Nora K. Schmid, using preliminary work by Angelika Neuwirth. Beta version: as of October 17, 2024

- ↑ Lane's Lexicon root: طرق Lane's lexicon - ṭarāiqa p 1848 & p 1849

- ↑ Lanes Lexicon root: فوق Lanes Lexicon - fawqa p 2460

- ↑ E.g. Tafsir Al-Jalalayn on verse 23:17; And verily We created above you seven paths, that is, [seven] heavens (tarā’iq is the plural of tarīqa [so called] because they are the paths used by the angels) and of creation, that lies beneath these [paths], We are never unmindful, lest these should fall upon them and destroy them. Nay, but We hold them back, as [stated] in the verse: And He holds back the heaven lest it should fall upon the earth [Q. 22:65]. & Tafsir Ibn Kathir on verse 23:17 also notes this refers to the seven heavens & Tafsir Maududi on verse 23:17 notes the seven visible moving 'planets' by the naked eye.

- ↑ Corpus Coranicum Commentary on Surah 23 Verse 17 Chronological-literary commentary on the Koran, Part 2: the Late Middle Meccan Surahs, edited by the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences by Dirk Hartwig and Angelika Neuwirth. Beta version: as of November 5, 2024

- ↑ E.g. Tanwîr al-Miqbâs min Tafsîr Ibn ‘Abbâs on verse 15:16. (Though the tafsir/commentary is attributed to Ibn Abbas, the prophets cousin, it is widely accepted to be at least largely a forgery - however it does give us an educated medieval Muslim's view on this verse).

- ↑ See Quranx on verse 15:16. Ahmad Khan has used 'towers' and Marmaduke Pickthall uses 'mansions'.

- ↑ Gabriel Said Reynolds. 1st Edition. The Qur'an and its Biblical Subtext. Copyright 2010. Published March 1, 2012 by Routledge 2012. ISBN 9780415524247. Taylor and Francis Group. A full in-depth analysis of the relevant verses and evidence stated for this meaning can be found on pp 114 - 131.

- ↑ Creation and Contemplation: The Cosmology of the Qur'ān and Its Late Antique Background (Studies in the History and Culture of the Middle East Book 47) Decharneux, Julien. 2023. (p. 313). De Gruyter.

- ↑ Mohammad Ali Tabatabaʾi and Saida Mirsadri, The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself pp. 208-210

- ↑ ..of all the kings of the children of Israel. And at length he forgot that he was a man, and he blasphemed and said, " I am God, and I sit upon the throne of God in the middle of the sea.' And Nebuchadnezzar the king killed him...THE BOOK OF THE CAVE OF TREASURES pp.127 TRANSLATED FROM THE SYRIAC TEXT OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM MS. ADD. 25875 BY SIR E. A. WALLIS BUDGE, KT. LONDON THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY. 1927.

- ↑ Minov, Sergey (2017). "Date and Provenance of the Syriac Cave of Treasures: A Reappraisal". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 20 (1): 129–229. doi:10.31826/hug-2018-200105.

- ↑ Patricia Crone pp. 309. Azaiez, Mehdi, Reynolds, Gabriel Said, Tesei, Tommaso and Zafer, Hamza M. et al. The Qur'an Seminar Commentary / Le Qur'an Seminar: A Collaborative Study of 50 Qur'anic Passages / Commentaire collaboratif de 50 passages coraniques, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110445909 (A free PDF download can be found on the page)

- ↑ Ibid. pp.306 & pp.314

- ↑ [1] مَقْعَدٌ / maqāʿida - Lane's Lexicon Classical Arabic Dictionary Book 1 p. 2547

- ↑ qāf ʿayn dāl (ق ع د) - Quranic Research Lane's Lexicon

- ↑ Penchansky, David. Solomon and the Ant: The Qur’an in Conversation with the Bible. Chapter 3 Surat-al-Jinn (The Jinn Sura) Q 72:1–19—War in Heaven (pp. 69-71). Cascade Books. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Penchansky discusses this topic on the academic "The Qur'an and the Bible" history YouTube channel with Professor Gabriel Said Reynolds: Origins of the Jinn in the Qur'an W/ Dr. David Penchansky

- ↑ Mohammad Ali Tabatabaʾi and Saida Mirsadri, The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself p. 212

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 212

- ↑ Tesei, Tommaso. Some Cosmological Notions from Late Antiquity in Q 18:60–65: The Quran in Light of Its Cultural Context. Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 135, no. 1, American Oriental Society, 2015, pp. 19–32, https://doi.org/10.7817/jameroriesoci.135.1.19.

- ↑ Where is Paradise and where is Hell? - IslamQA.info

- ↑ E.g. Tanwir al-Miqbas min Tafsir Ibn Abbas on verse 95:4-6.

- ↑ jannah | garden Sinai, Nicolai. Key Terms of the Qur'an: A Critical Dictionary (p. 195). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Ibid. pp 195-196.