Histoire de la transmission du Coran

This article or section is being renovated. Lead = 4 / 4

Structure = 4 / 4

Content = 4 / 4

Language = 4 / 4

References = 4 / 4

|

This article examines the transmission history of the Quran. The perfect preservation of the Quran is an article of faith for most schools and sects of Islam and figures highly in the beliefs of Muslims around the divine nature of their religion. Orthodox Islamic scholars argue that the Qur'an today is identical to that received by Prophet Muhammad. This contention however is challenged both by parts of the Islamic tradition itself and the findings of modern scholarship.

Before Caliph Uthman standardised the Quranic consonantal text (QCT) around 650 CE, large numbers of variants later documented by Muslim scholars were read by various companions of Muhammad, often differing in whole words and phrases. Academic experts have found material support for such reports in some of the oldest Quran manuscripts. There are also hadith reports that substantial numbers of verses had already been lost. The fear of permanently losing verses is said to have motivated the initial collection of the Qur'an under Caliph Abu Bakr. Notwithstanding a number of scribal errors during the initial copying process, Uthman was essentially successful in stabilising the QCT, or rasm. However, due to limitations in the early stage of Arabic orthography in use at that time, a wide variety of oral readings (qira'at) within this standardised rasm was possible. This continued until the oral readings too were stabilised over centuries and orthography developed to more fully document them. Tens of thousands of variants are attributed to readers of the first couple of centuries, which include Muhammad's companions and early reciters, within and outside the standard rasm, besides those found in the ten canonical readings and their transmitters. The vast majority of recitation and printed Qurans in use today are based on the transmission of Hafs from the reading of 'Asim.

Introduction

The Qur'an is claimed to be a revelation from Allah to Prophet Muhammad through the Angel Gabriel. It was revealed to Muhammad in stages, taking 23 years to reach its completion.

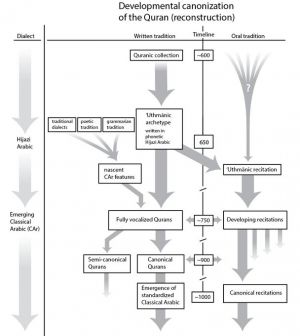

The textual and oral transmission history of the Quran are interconnected. As discussed in this article, standardisation first occured in the written consonantal skeleton. This acted as a constraint on the variant oral readings (qira'at), which too eventually became standardised and written down in stages. This was accomplished by Muslims over a period of many centuries. Muslims would argue that the Qur'an was preserved by Allah, who promised to "guard it"[2] and that "none can change his words".[3]

Earliest Collection of the Quran

Unfortunately, at no time during Muhammad's life did he ever order the Quran to be compiled into a single book. A detailed hadith records that many Qurra' (“reciters”) had died before the Quran had been compiled in written form, so Abu Bakr asked Zaid bin Thabit to collect it into a book. Zaid was reluctant, for Muhammad had never ordered such an action to be taken. He stated, "I started looking for the Qur'an and collecting it from (what was written on) palm-leaf stalks, thin white stones, and also from the men who knew it by heart, till I found the last [two] verse[s] of Surat at-Tauba (repentance) with Abi Khuzaima al-Ansari, and I did not find it with anybody other than him. [...] Then the complete manuscripts (copy) of the Qur'an remained with Abu Bakr till he died, then with `Umar till the end of his life, and then with Hafsa, the daughter of `Umar."[4]

The story that the Quran had yet to be collected together when Muhammad died might conflict with two (slightly contradictory) accounts collected in Sahih Bukhari, although scholars have noted that the verb jama'a (جَمَعَ) can also mean memorized:

Narrated Anas bin Malik:

When the Prophet died, none had collected the Qur'an but four persons: Abu Ad Darda, Mu'adh bin Jabal, Zaid bin Thabit and Abu Zaid. We were the inheritor (of Abu Zaid) as he had no offspring .Muhammad's Own Recollection of the Verses

While even today there are many memorizers (huffaz) of the complete Qur'an, the earliest Muslims did not have the benefit of choosing a standard qira'at (reading) and standard written Qur'an complete with diacritics in book form to help them or their teachers in the learning process.

The Qur'an itself records that Muhammad himself had forgotten portions of the Qur'an[5][6] Muhammad may also have had a somewhat flexible approach to variant readings, typical of oral performance traditions - see the Qira'at section later in this article.

Hadiths too attest that Muhammad himself forgot parts of the Qur'an and needed his followers to remind him:

In the below hadith it seems Muhammad's companions also forgot passages of the Qur'an:

Companion Codices and the Uthmanic Standard

Caliph Uthman Standardises the Rasm and Burns the Other Texts

A widely transmitted hadith reports that the third caliph Uthman was concerned because there were clear differences in the recitation of the Qur'an among the people of the Sham (modern day Israel/Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria) and the people of Iraq. The differences were so great Uthman and his companions feared future dispute about the true Qur'an and its contents. So Uthman asked Hafsa for her copy so that a committee could write a single version of the rasm (an early stage of Arabic orthography, often called the Qur'anic consonantal text (QCT), which lacked most word-internal ʾalifs, lacked diacritics such as short vowel signs and with scarce use of dotting to distinguish certain consonants). Uthman then sent out his official Quranic codex to a small number of important cities and ordered that all other copies and fragments be burned. This occurred around 650 CE. During the prior 20 years since Muhammad's death, and for some time afterwards, thousands of variants read by the companions which often did not fit this rasm were in circulation, as documented in hadiths and works such as Ibn Abi Dawud's Kitab al Masahif.[7]

Narrated Anas bin Malik:

Uthman (or 'Abd al-Malik b. Marwan) destroys Zayd's original Qur'an compilation

The above quoted hadith of the Uthmanic standardisation was found by Harald Motzki to be very early.[8] His analysis of isnads (transmission chains) matched with changes to the matn (content) showed it to be widely transmitted through the common link of Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī (d. 124). It mentions that Hafsa allowed Uthman to borrow and return the Qur'an manuscripts (ṣuḥuf الصُّحُفُ) in her possession. They were also mentioned in the hadith about the initial collection of the Qur'an quoted further above, which says she had inherited them after they were compiled by Zayd ibn Thabit under Abu Bakr twenty years earlier (this too was widely transmitted through al-Zuhri, and considered by Motzki to be very early for the same reason).[4].

However, some time after standardisation and her death, they were handed over to the Caliph by her brother and deliberately destroyed. Sean Anthony and Catherine Bronson note: "Zuhrī—the earliest known scholar to emphasize the importance of Ḥafṣah’s codex for the collection of the caliph ʿUthmān’s recension—also serves as the authority for the accounts of the destruction of Ḥafṣah’s scrolls (ṣuḥuf). Hence, we are likely dealing with two intimately intertwined narratives that originated with Zuhrī and his students." On the identity of the Caliph, they note "at least four versions of the Zuhrī account assert that the caliph ʿUthmān (and not Marwān) requested ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar to hand over Ḥafṣah’s muṣḥaf after his sister’s death, whereupon the codex was either burned or erased." In the other versions, "Marwān has the codex either erased by washing the parchment (ghasalahā ghaslan), torn to shreds (shaqqaqahā wa-mazzaqahā), or burned to ashes (fashāhā wa-ḥarraqahā)" and "Marwān himself cites 'the fear that there might be a cause to dispute that which ʿUthmān copied down because of something therein.'"[9]

For the academic debate regarding whether the Quranic text was standardised under Uthman or 'Abd al-Malik see the dedicated section below.

Disagreements on the Qur'an

Sahih hadiths and tafsirs record a great many variations of recitation among the sahaba (companions) for many different verses.

- An example involving multiple companions is found in two consecutive verses. Bukhari and Muslim record that Ibn 'Abbas and Sa'id b. Jubair respectively added the word "servicable" to describe the boats in Quran 18:79, and added the words, "the boy was an unbeliever" to Quran 18:80.[10][11] Al Tabari's tafsir for these verses include reports that Ibn Mas'ud too recited them this way.

- Another interesting example, recorded in a sahih hadith that appears in many collections, concerns a variant reading of verse Quran 2:238. It was given by Aisha, according to whom in this verse it says 'the middle prayer and the Asr Prayer', as she heard Muhammad reciting it.[12] As such, her version of the verse combines what was, according to another hadith, the pre-abrogated version of the verse, which mentions the asr prayer, and post-abrogation version, which says the middle prayer.[13]. What purpose would be served by an abrogation to replace one specific word with another that more ambiguously indicates the same prayer (according to most scholars) is a mystery.

- An interesting example of companions still reciting a verse allowing a practice that was supposed to have been abrogated concerns the controversial topic of nikaah al-mut'ah (temporary marriage), which Muhammad banned in his final years according to sahih hadiths (some use other hadiths to argue that instead Umar did so after his death), and verse 4:24, which says:

- ...Then as to those whom you profit by, give them their dowries as appointed; and there is no blame on you about what you mutually agree after what is appointed; surely Allah is Knowing, Wise.

- Al-Tabari's tafsir for verse 4:24 includes narrations saying that Ibn 'Abbas, Ubayy ibn Ka'b, and Sa'id ibn Jubayr (others too in other tafsirs) included the words 'until a prescribed period' ('ila ajal musamma') after the words 'whom you profit by'.

Some Muslim scholars sought to explain the reported differences in the mushafs (codices) of the companions as merely being their own exegetical glosses. Such an explanation may be possible in some instances, but certainly not in others such as when pronouns or grammatical forms are changed or words are reported to have been simply omitted, for example in Quran 112:1 where Ibn Mas'ud and Ubayy omitted the word "Say" (qul)[14][15], or Ibn Mas'ud's omission of the entire verse Quran 94:6.[16][17] Other explanations were that these were variations in the revelation ("ahruf", discussed in a section below) or abrogated versions of the verses, which encounter some of the same problems as just mentioned, as well as the issue of their sheer quantity and the difficulty of explaining the purpose of the less clear or specific wordings of the same sentences in the Uthmanic Qur'an.

Many other examples of such variations among the sahaba are discussed in another online article and in the next few sections below.[18] A full translation of the variants documented in Abu Ubayd's (d. 244 H.) Fudail al-Quran is also available.[19]

Qur'an of Ibn Mas'ud

It was widely reported that Abdullah ibn Mas'ud's Qur'anic text omitted surah al-Fatiha and the mu'awwithatayni (surahs 113 and 114).[20][21] Ibn Mas'ud's denial that the last two surahs were part of the Qur'an is also recorded in Sahih Bukhari.[22]

When we come to the rest of the Qur'an, we find that there were numerous differences of reading between the texts of Zaid and Ibn Mas'ud. The records in Ibn Abu Dawud's Kitab al-Masahif fill up no less than nineteen pages[23] and, from all the sources available, one can trace no less than 101 variants in the Surah al-Baqarah alone.[24]

The following are just a few of the differences in illustration of the nature of the variations between the texts:

- Sahih Bukhari 6:60:468 and Sahih Muslim 4:1799 both record that Ibn Mas'ud's followers were adamant that he and Muhammad had read Quran 92:3 with the words, By the male and the female. rather than And by Him Who created male and female.

- Quran 2:275 begins with the words Allathiina yaakuluunar-ribaa laa yaquumuuna, meaning "those who devour usury will not stand". Ibn Mas'ud's text had the same introduction but after the last word there was added the expression yawmal qiyaamati, that is, they would not be able to stand on the "Day of Resurrection".

- The variant is mentioned in Abu Ubaid's Kitab Fadhail al-Qur'an.[25][26][27] The variant was also recorded in the codex of Talha ibn Musarrif, a secondary codex dependent on Ibn Mas'ud's text, Talha likewise being based at Kufa in Iraq where Ibn Mas'ud was based as governor and where his codex was widely followed.[28]

- Quran 5:89, in the standard text, contains the exhortation fasiyaamu thalaathati ayyaamin, meaning "fast for three days". Ibn Mas'ud's text had, after the last word, the adjective mutataabi'aatin, meaning three "successive" days.[29]

This variant is recorded by al-Tabari and was also mentioned by Abu Ubaid and al Zamakhshari.[30] This variant reading was, significantly, found in Ubayy ibn Ka'b's text as well[31] and in the texts of Ibn 'Abbas[32] and Ibn Mas'ud's pupil Ar-Rabi ibn Khuthaim.[33] Ibn Mas'ud's reading was used by Hanafi scholars to rule that the fasting must be on successive days while Shafi scholars said this was not necessary. This and other Ibn Mas'ud variant readings used in Hanafi jurisprudence (such as restricting hand amputation to right hands) are discussed by Dr Ramon Harvey.[34]

Pre-eminent status of Ibn Mas'ud as a reciter of the Qur'an

Muhammad ordered Muslims to learn the Qur'an from four individuals and the first of them was Abdullah ibn Mas'ud.[35] So, according to Muhammad, Ibn Mas'ud was an authority on the Qur'an.

Ibn Mas'ud swore that he knew all the surahs of the Qur'an, saying "By Allah other than Whom none has the right to be worshipped! There is no Sura revealed in Allah's Book but I know at what place it was revealed; and there is no verse revealed in Allah's Book but I know about whom it was revealed. And if I know that there is somebody who knows Allah's Book better than I, and he is at a place that camels can reach, I would go to him".[36]

After Muhammad's choice of Abdullah bin Mas'ud, he was followed by Salim, the freed slave of Abu Hudhaifa, Mu'adh bin Jabal and Ubai bin Ka'b.[35]It is notable that we do not find any mention of Zayd Bin Thabit who was ultimately entrusted by Abu Bakr with the task of collecting the Qur'an and later or alternatively as part of Uthman's Committee.

Ibn Mas'ud's Disagreement with Uthman

The Qur'an that Ibn Mas'ud had was known and agreed upon by many Muslims in Kufa. When Uthman ordered that all codices must be destroyed and that only Zayd's codex is to be preserved, the reaction of Abdallah ibn Mas'ud was defensive.

"I have not led them [the people of Kufa] astray. There is no verse in the Book of Allah that I do not know where it was revealed and why it was revealed, and if I knew anyone more learned in the Book of Allah and I could be conveyed there, I would set out to him".[37]

A hadith graded sahih appears in al-Tirmidhi's collection. After mentioning Uthman's attempts to enforce a codice (mushaf), we read:

Similar comments from Ibn Mas'ud are recorded elsewhere.[38][39]

Dr. Ramon Harvey writes, "The sources point to no less than a century of Kufan resistance to the imposition of a canonised Qur’anic text, with Ibn Masʿud’s variant readings openly used in ritual prayer and even taught as the dominant tradition."[34]

Qur'an of Ubayy bin Ka'b

Ubayy ibn Ka'b, was another one of the four which were singled-out by Muhammad,[35] and was considered the best reciter of the Qur'an.[40] He was known as Sayidul Qura' (The Master of Reciters). Umar the Caliph also agreed that Ubayy was the best reciter, even though he rejected some of what he recited, and said that Ubayy refused to change his recitation.[41] As detailed in another section below, Ubayy had 116 surahs in his codex, two more than the Uthmanic Qur'an.

Some examples where Ubayy agreed with Ibn Mas'ud and disagreed with Zayd include the following:

- In Quran 22:78 the standard reading says "the faith of your father Abraham (is yours). He hath named you Muslims". In Ubayy's reading, the somewhat ambiguous "He" (huwa) is replaced with "Allah".[42][43]

- In the standard reading of Quran 39:3 the polytheists say "We worship them" (na'buduhum), whereas Ubayy read them saying "We worship you (plural)" (na'budukum).[44][45]

- There are a number of cases where whole clauses differed in his text. In Quran 5:45, where the standard text reads wa katabnaa 'alayhim fiiha, meaning "and We inscribed therein for them (the Jews)", the reading of Ubayy ibn Ka'b was wa anzalallaahu alaa banii isra'iila fiiha, meaning "and Allah sent down therein to the Children of Israel."[46][47] This is similar to the lower text of the Sanaa 1 palimpsest, which reads here "wa katabnaa alaa banii isra'iila".[48]

Qur'an of Ibn 'Abbas

Among the many examples of different readings attributed to Ibn 'Abbas are the following (further to those already mentioned above).

- Sahih Muslim[49] and Sahih Bukhari[50] record that Ibn 'Abbas read verse Quran 26:214 with the additional words, "and thy group of selected people among them".

- Ibn 'Abbas is widely reported in al Tabari's tafsir to have said that "ascertain welcome" (tasta'nisu) in Quran 24:27 was a scribal error, and instead should say "ask permission" (tasta'dhinu), a subtly different meaning in Arabic. This narration was also reported elsewhere and classed sahih by al-Hakim, Dhahabi and Ibn Hajar[51]. Ubayy and Ibn Mas'ud (the latter with different word order) are also reported in al-Tabari's tafsir to have read tasta'nusu. The Ibn Mas'ud wording (except singular instead of plural) is also found in the lower text of the Sana'a palmpsest.[52]

- He also regarded "Your Lord has commanded" (waqada rabbuka) in Quran 17:23 to be a scribal error which should have read "And your Lord has advised" (wawassa rabbuka)[53][54], as was the reading of Ubayy, ibn Mas'ud and others according to al-Tabari.[55]

- Ibn 'Abbas instructed that Quran 2:137 should be read "And if they believe in that (āmanū bimā) which ye believe" instead of the standard Uthmanic "And if they believe in the like of that (amanū bi-mithli mā) which ye believe". Dr. Hythem Sidky notes that "This variant is recorded as being found in the muṣḥafs of the Companions Ibn Masʿūd and Anas b. Mālik and the Successor Abū Ṣāliḥ. Ibn ʿAbbās is also reported to have disliked the ʿUthmānic reading, which contains bi-mithl, as he considered God to have 'no equivalent (laysa lahū mathīl).'" Sidky notes that the āmanū bimā reading was also attested in the early manuscript BnF Arabe 331.[56] The opinion of Ibn Abbas is noted in al-Tabari's tafsir for this verse.

Extant Early Manuscripts

A significant number of early Hijazi manuscript fragments have been radio-carbon dated to the first Islamic century, collectively covering the Qur'an between them (for a detailed discussion with images, see the article by Michael Marx and Tobias Jocham[58]).

All but one of the early Quran manuscripts discovered so far have been of the Uthmanic text type (the exception being the lower text of the Ṣan'ā' 1 manuscript, which is a palimpsest (codex which was washed and written over) found in Sana'a, Yemen, and which contains variants not found in any of the accepted readings of the Qur'an.[59]). However, these manuscripts are not identical. Every early manuscript falls into a small number of regional families (identified by variants in their rasm, or consonantal text), and each moreover contains non-canonical variants in dotting and lettering that can sometimes be traced back to those reported of the Companions.[60] The Ṣan'ā' 1 manuscript is especially known to have this feature.[61][62][63]

Michael Cook's stemmatic analysis of the above mentioned regional variants reported in the Uthmanic copies has shown that they form a tree relationship[64]. By analysing orthographic idiosyncrasies (i.e. spellings) common to known manuscripts of the Uthmanic text type, Dr. Marijn van Putten has given further proof that they all must descend from a single archetype, generally assumed to be that of Uthman.[65]

He has noted that the famous "Birmingham Quran" too has these spelling idiosyncracies and therefore is "clearly a descendant of the Uthmanic text type".[66] It is a two page fragment (Minghana 1572a), now known to be part of a longer manuscript fragment held in Paris (BNF Arabe 328c). In her PhD thesis, Alba Fedeli showed that the combined manuscript contains numerous variants, including some which affect meaning (especially the subject or object of verbs) and a few that had been reported in the qira'at literature. These mainly involve alifs and the sparse consonantal dottings present in the manuscript.[67]

A few famous manuscripts have been traditionally attributed as Uthman's personal copy, or as one of the original copies he commissioned. None of these claims is supported by evidence. These include the Topkapi manuscript (Sarayı Medina 1a) which has too late a script style, and the Samarkand Codex, which is actually radio-carbon dated to the 8th or 9th century CE, as well as due to the script style.[68]

The rasm is only part of the story of the textual transmission of the Qur'an. In the earliest Quran manuscripts (and, we can assume, in the fragments originally collected by Zayd), homographic Arabic consonants were only sparsely dotted to distinguish them, which Adam Bursi has found was the typical scribal practice at that time even for Arabic poetry.[69] They also lacked most word-internal ʾalifs (unwritten or inconsistent usage in most situations), and had no marks for short vowels or other diacritics. When vocalised manuscripts with vowels and other diacritics start to appear, many (mostly non-canonical) readings are found to be imposed upon the rasm.[70]

Scribal errors in Uthman's codices

Academic scholars generally believe that the above mentioned regional variants were scribal errors made when the original copies of Uthman's consonantal text were produced. These feature also in the canonical readings (qira'at) of those regions, which were required to keep within the scope of the Uthmanic text. These scribal errors in the original Uthmanic copies have been inherited by all subsquent copies of the Quran that exist in the world, as distinct from isolated mistakes in individual manuscripts. For example, Qurans in North Africa which typically have the reading of Warsh from Nafi will have the text of the Uthmanic copy given to Medina.

The strongest tradition holds that four copies were made, one each for Medina in the Hijaz, Syria (Hims, or less likely, Damascus[71]), Basra and Kufa in modern day Iraq. As mentioned above, Michael Cook identified that these 40 or so variants form a stemmatic relationship that indicates a written copying process between the four codices.[64] His list was based on al-Dani's work (d. 444 AH) and can also be read online in a paper by van Putten.[72] Compiling a similar but improved list of the regional variants widely attested by Muslim scholars, Hythem Sidky reconstructed the same stemma as found by Cook for what must have been four regional exemplar codices.[71] This is mainly derived due to the twelve variants shared by Syria and Medina to the exclusion of Basra and Kufa, fifteen isolated Syrian variants and three isolated Kufan variants.[73] Sidky also found an "excellent agreement" between these reports and the earliest manuscripts. In additon, Sidky was able to reproduce the stemmatic result by means of a phylogenetic analysis of these regional differences within the earliest manuscripts (except that Kufa did not achieve a separate node since only one early Kufan manuscript is available). Sidky also found that "a comparison of literary reports against the earliest manuscripts reveals that knowledge of the regional variants does not date back to the time of canonization but was accumulated over time through careful scrutiny of regional muṣḥafs". This indicates that the Uthmanic committee were unaware or did not share information about these differences. He has also commented separately on this topic that further reasons for believing them to be scribal errors are that they are so few in number in what were obviously and reportedly intended to be identical copies, and that they are so insignificant, looking like typical scribal errors that occur in later copying, especially compared to the kinds of more meaningful variants found in companion readings (see earlier section on these above).[74]

Academic debate regarding Uthman or 'Abd al-Malik

In the early 20th century, a few academic scholars proposed that the consonantal text of the Quran reached its final form not under Uthman, but rather half a century later under 'Abd al-Malik b. Marwan and his enforcer, al-Hajjaj around 700 CE. Going further, in the 1970s John Wansbrough advocated a late 8th century CE compilation. Subsequent insights such as Motzki's work on the al-Zuhri hadiths and the radio carbon dating of early manuscripts including Sanaa 1 (both discussed above) have eliminated Wansbrough's more extreme view, though a debate continues between those arguing that the Quranic consonantal text as we know it was standardised under Uthman and those skeptical that this could have happened, instead dating it to the Caliphate of 'Abd al-Malik. This debate and evidence drawn by each side is best exemplified in a two part 2014 article by Nicolai Sinai (both parts are accessible with a free JSTOR account, selecting "Alternative access options"),[75] siding with the Uthmanic viewpoint, and an open access book published in 2022 by Stephen Shoemaker advancing the 'Abd al-Malik theory, and which also responds to Sinai's articles.[76] Shoemaker interprets some Muslim as well as Christian accounts about 'Abd al Malik and al-Hajjaj in support of his view, with the Uthmanic story (traced as far back as al-Zuhri, as discussed above) being a back-projection to lend a more credible lineage to the project. Sinai instead interprets accounts about al-Hajjaj such that he was enforcing Uthman's standard (see the section on al-Hajjaj below). The 'Abd al-Malik camp also contend that their theory is the best explanation for various other strands of evidence.

Since Sinai's articles, further evidence in support of an Uthmanic standardisation has been identified by van Putten proving that all known Quranic manuscripts (except Sanaa 1) must descend from a single archetype (see above). Shoemaker notes van Putten's evidence could fit either theory. However, the archetype necessarily would have to be earlier still than the earliest surviving manuscripts or fragments. This seems to favour an Uthmanic codification, since while Shoemaker and others are very critical of the reliability of manuscript radio carbon dating, the paleographic dating (study of handwriting and ornamentation, supported by dated inscription evidence) would also have to be later than supposed to allow time for a c. 700 CE archetype. Defenders of radio-carbon dating would point out that the three most reputable testing laboratories in the world (Arizona, Zurich and Oxford) concur on a first half of the 7th century date for the Sanaa 1 palimpsest, the most repeatedly tested Quranic manuscript. Another subsequent consideration must be van Putten's work on the Hijazi dialect of the QCT (see below and pages 220-221 of his book), which fits al-Zuhri's account that Uthman instructed for the codices to be written in the Quraysh dialect. Hythem Sidky's work published in 2021 (see above) confirms that four regional exemplar codices were sent out and found that the Syrian codex was likely sent to Hims (modern day Homs) rather than Damascus (as sometimes assumed, with virtually no evidence). Among other evidence he notes that a Hims copy fits a version of the Uthmanic codification account recorded by Sayf b. ʿUmar al-Tamīmī (d. ca. 180/796). It could also perhaps be argued that an Umayyad standardisation would have first ensured that one of the few exemplar copies would go to Damascus had it occured under their reign since this had been their power base since Mu'awiya (661 CE). Also of likely relevance is that in 2006, Fred Leemhuis noted that the Dome of the Rock (built 692 CE) exhibits a probably short-lived orthographic convention in which the letter qaf was distinguised by a dot below the line, and that this convention is also found in four of the oldest Quran manuscripts.[77]

Lost Verses and Surahs from the Qur'an

Professor Yasin Dutton briefly lists several examples in Islamic literature of differences "involving the addition or omission of substantial amounts of material, such as an āya or even a sūra".[78] These examples and one or two others are explored in this section.[79]

The lost verse on stoning

There are claims in the hadith that certain verses are missing. For example the 'stoning verse' for adultery. The present day Qur’an does not contain the penalty of Rajm (stoning) for married adulterers, which abrogated the previous penalty. Rather, the Qur'an now extant assigns whipping as the punishment for adultery:

The lost verse of Rajm (stoning) was originally found in Surah al-Ahzab[80]. According to hadiths recorded in Al-Suyuti's Itqan the lost verse read, "The fornicators among the married men (ash-shaikh) and married women (ash-shaikhah), stone them as an exemplary punishment from Allah, and Allah is Mighty and Wise,", or alternatively, "A married man or woman should be stoned, without hesitation, for having given in to lust." [81]

This verse, along with verses regarding adult suckling, were reportedly written on a piece of paper and were lost when a sheep or goat ate them.[82] The loss of the stoning verse is confirmed by Caliph Umar in sahih hadith in which this verse is said to have been included in the book "sent down" to Muhammad, "the Book of Allah".[83] In another sahih hadith appearing in many collections[84], Muhammad says he will judge a married woman who committed adultery with an unmarried man by "the Book of Allah" (meaning the Qur'an[85]) and orders the woman to be stoned and the man to receive 100 lashes. Before becoming lost, the verse on adult suckling had already been abrogated and replaced with a watered down version. Evidently it was not very popular, and was resisted by some of Muhammad's wives.[86]

Islamic scholars typically explain the loss of the stoning verse as a type of abrogation where the verse is no longer recited but the ruling still applies. Al-Suyuti in his Itqan gives various hadiths in which Muhammad and the Muslim community felt uneasy about writing down, and possibly even reciting such a harsh verse, having witnessed its implementation.[87] It seems that as a result even the recitation of the exact wording for this verse was lost over time. It is unclear how this is compatible with preservation by calling it abrogation even though the ruling remains, particularly when it involves such a serious topic as a death penalty.

Most of Surah al-Ahzab was lost

It seems that the verse on stoning was not the only one to disappear from surah al-Ahzab.

With sahih isnads appearing in many hadith collections via ‘Aasim ibn Bahdalah, from Zirr, we have this hadith:

قال لي أبي بن كعب : كأين تقرأ سورة الأحزاب أو كأين تعدها قال قلت له ثلاثا وسبعين آية فقال قط لقد رأيتها وإنها لتعادل سورة البقرة ولقد قرأنا فيها الشيخ والشيخة إذا زنيا فارجموهما البتة نكالا من الله والله عليم حكيم

Narrated ‘Aasim ibn Bahdalah, from Zirr, who said:

Ubayy ibn Ka‘b said to me: How long is Soorat al-Ahzaab when you read it? Or how many verses do you think it is? I said to him: Seventy-three verses. He said: Only? There was a time when it was as long as Soorat al-Baqarah, and we read in it: “The old man and the old woman, if they commit zina, then stone them both, a punishment from Allah, and Allah is Almighty, Most Wise.”

[88]Islamqa.info, the popular fatwah website accepts the hadith and that the verses were lost on the authority of the scholars. Its isnad was graded by al-Tabari and al-Albani as sahih, even more emphatically by Ibn Hazm, “sahih, as clear as the sun” (إسناده صحيح كالشمس), and hasan (good) by Ibn Kathir and Ibn Hajar.

Corroborating evidence is given by Qurtubi at the beginning of his tafsir for Surah al-Ahzab. He records this recollection by 'A'isha, although the chain includes Ibn Lahee'ah, who many consider weak for having an unreliable memory:

“Aisha narrates: ‘Surah Ahzab contained 200 verses during the lifetime of Prophet [s] but when the Quran was collected we only found the amount that can be found in the present Quran (ie 73 verses)".

[89]Surah al-Hafd and Surah al-khal'

We know that, whereas Ibn Mas'ud omitted three surahs (al-Fatihah, 113 and 114) from his Qur'an mushaf (codex), Ubayy ibn Ka'b had 116 surahs in his, including two extra short surahs, al-Hafd (the Haste) and al-Khal' (the Separation), which he placed between what are surahs 103 and 104 in Uthman's Qur'an[90].

In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.

O Allah, You alone we worship,

to You we pray and prostrate,

and for Your sake we work and strive.

We hope for Your mercy and fear Your punishment,

for Your punishment will inevitably befall the disbelievers.

al-Khal':

In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.

O Allah, verily we seek Your help and Your forgiveness,

and we praise You and we are not ungrateful to You.

And we disavow and disown anyone who opposes You. [91]

[92][93][94]In form they are du'as (supplications, prayers), much like Al-Fatihah placed at the beginning of the Qur'an, and surahs 113 and 114.

Professor Sean Anthony has noted in a detailed paper on the topic that "the literary attestations for the inclusion of al- Khalʿ and al-Ḥafd in written copies of Ubayy’s codex are multiple, coherent, and geographically widespread – a fact that speaks volumes in favor of their authenticity." and that according to some early sources, Ibn Mas'ud too included Khal' and Hafd in his Qur'an mushaf (codex)[95], as also did Ibn 'Abbas in his mushaf, though its presence in Ubayy's is much more widely documented.[96] One hadith records that Uthman recited them as supplications [97], as did Umaya bin Abdullah and Umar according to Al-Suyuti.[94] Another hadith says that these were du'as given by the angel Jibreel to Muhammad.[98] Al-Suyuti quotes another scholar saying that Surah al-Khal' and Surah al-Hafd were removed from the Qur'an and are now used as du'as.[99][100]

It doesn't seem that there was agreement among the Muslims on whether these were just du'as or parts of the Qur'an, particularly given that such an important figure as Ubayy ibn Ka'b (possibly Ibn Mas'ud and Ibn 'Abbas too) recorded them in his widely reported Qur'an codex.

Nor does it seem there was complete agreement on whether other surahs that resemble du'as belonged in the written Qur'an given that Ibn Mas'ud left out of his mushaf Surahs Al-Fatihah, and 113 and 114 (called Al-Mu'awwidhatan), as mentioned above. Al-Qurtubi's tafsir contains a narration from Ibn Mas'ud that he omitted Al-Fatihah for brevity[101], and there was a theory to explain his omission of surahs 113 and 114[21].

The canonical Qira'at (recitations of the Qur'an) of the Kufan readers include all 3 surahs yet have Ibn Mas'ud in some chains of their isnads. A common apologetic argument is that therefore Ibn Mas'ud must have included all three surahs in his Quran. However, the isnads to each of the Kufan readers also include transmissions that do not go via Ibn Masud. Moreover, it is known that the canonical reader Hamza (on whose reading also two other Kufan readings depend) made use of Ibn Mas'ud's readings (via his teacher, al A'mash) only insofar as they complied with the Uthmanic rasm.[102]

Sometimes the 14th century scholar Muhammad Abdul Azim al-Zurqani is quoted, who suggested that the companions who included Al-Hafd and Al-Khal' in their Qur'an mushafs were merely noting them down as du'as alongside the Qur'an, and that this had led to the confusion over whether they were considered Qur'anic. But it is a very unlikely theory that Ubayy ibn Ka'b (and possibly other companions) who recorded these surahs in his mushaf would allow such a misunderstanding to occur. We have two independent lists saying that Ubayy ibn Ka'b sequenced these two du'as between what are now surahs 103 and 104.[90]

Some argue that Ubayy ibn Ka'b must have had no issue with the two extra surahs being left out because there is a hadith recorded 9 centuries after Muhammad, which says that Uthman had Ubayy dictate the text for Zaid to write down, with refinements by Sa’id bin al-‘Aas[103]. Such evidence is very late, as well as contradicting sahih hadiths about Zaid's collection process.

The Missing Surah with the Two Valleys

Abu Musa al-Ash'ari, one of the early authorities on the Qur'an text and a companion of Muhammad, claimed a surah which resembled at-Tawba (also known as Bara'at) in length and severity was forgotten and lost, but included a passage on the greed of man, which is not in today's Qur'an. Various narrations have slightly differing wording for this lost passage, which is consistent with it being insufficiently remembered.

Ibn Abbas was likewise unsure whether it was part of the Qur'an or not:

Ubai said that it was considered as a saying from the Qur'an for a while during Muhammad's lifetime. At best, it could be claimed to be an example of a type of abrogation where the verses are lost. Why the verse would be abrogated is unexplained.

Al-Suyuti records the recollection by Abu Waqid al-Laithii of the occasion when the lost passage about the valleys was revealed. He says that Muhammad claimed it as a revelation from Allah, just like when he received other revelations.[104]

Lost verses from Surah at-Tawba

Surah at-Tawba (also known as al Bara'at) was originally equal to the length of al-Baqara according to narrations recorded by al-Suyuti (best known for his Tafsir al-Jalalayn) in The Itqan[105] and Tafsir al-Qurtubi[106]. In a Hasan hadith in the collection of Tirmidhi, Uthman is narrated as saying that they didn't know whether or not Surah at-Tawba was part of Surah al-Anfal, and Muhammad died without making it clear, so they were placed together.[107]

The "Bring a surah like it challenge"

As detailed in the sections above, there were non-Qur'anic surahs and verses that sounded very much like those of the Qur'an. Surah al-Hafd and Surah al-khal', and the verses about Adam and the valleys sounded so Qur'anic that they were at one time believed to be so by speakers of 7th century Arabic, Sahabah no less. Theories that these were once part of the Qur'an and later abrogated, or that Al-Hafd and Al-Khal' were du'as given to Muhammad by Jibril do not give a reason why they may have been abrogated or why confusion was allowed to arise about the status of the latter two when they were recorded in the mushaf of Ubayy (and perhaps other companions).

The Qira'at (Variant Oral Readings of the Qur'an)

As mentioned above, numerous possible oral readings of the Qur'an can be and were imposed upon the Uthmanic rasm (an early stage of Arabic orthography, which lacked diacritics such as short vowel signs, most word-internal ʾalifs, and with scarce use of dotting to distinguish certain consonants). Today we have seven or ten canonical qira'at, which are slightly different early oral recitations or readings of the Qur'an by famous readers. There were once many more qira'at, from which twenty-five were described by Abu 'Ubayd al-Qasim ibn Sallam two centuries after Muhammad's death, and restricted to seven after three centuries following a work by Abu Bakr ibn Mujahid (d.936 CE). A further three qira'at were added to the canon many centuries later by Ibn al-Jazari (d.1429 CE) - those of Abu Jafar, Ya'qub and Khalaf. These three had been popular since the time of the seven[108], and provide additional variants.[109] Some scholars regarded them as having a somewhat less reliable transmission status than the seven.[110] Ibn al Jazari lamented that the masses only accepted the seven readings chosen by Ibn Mujahid.[111]

The authenticity of the canonical readings became an important issue to affirm. Al Zarkashi (d.1392 CE) argued that even the differences in the canonical readings are mutawatir (mass transmitted from the time of Muhammad), despite each reading only having one or a small number of single chains of purported transmission between Muhammad and the eponymous reader, because the inhabitants in the cities in which they were popular also heard them. Professor Shady Nasser finds it hard to accept al Zarkashi's argument since in that case "variants within one Eponymous Reading should not have existed" (i.e. students of a particular reader often did not transmit identically), as well as due to the presence of multiple popular readers in each city.[112] As noted above, most canonical readings are not found in early vocalised manuscripts. To secure the status of the three readings after the seven, Ibn al-Jazari obtained a fatwa from Ibn al Subki declaring that all 10 readings were fully mutawatir, though later he changed his mind.[113]

Each of the Qira'at has two canonical transmissions (riwayat) named after its transmitters, one of which is the basis for any particular text (mushaf) of the Qur'an. For example, the mushaf used mainly in North Africa is based on the riwayah of Warsh from Nafi (the reading of Nafi transmitted by Warsh). As Nasser explains, the two-Rawi canon for ibn Mujahid's choice of seven readings was effectively canonized due to the popularity both of a simplified student Qira'at manual by al-Dani (d.1053 CE; who in another more complicated work documents a larger range of transmissions for each reader), and a poetic form of this manual by al-Shatibi (d.1388 CE).[114] The canonical transmitters all differ in their readings, even when they transmit from the same reader. This two transmitter system was expanded when Ibn al Jazari canonized the three readers after the seven mentioned above, giving twenty canonical transmitters for the ten readers in total.

| Qari (reader) | Rawi (transmitter) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Born | Died | Name | Born | Died | |||||

| Nafi‘ al-Madani | 70 AH | 169 AH (785 CE) | Qalun | 120 AH | 220 AH (835 CE) | |||||

| Warsh | 110 AH | 197 AH (812 CE) | ||||||||

| Ibn Kathir al-Makki | 45 AH | 120 AH (738 CE) | Al-Buzzi | 170 AH | 250 AH (864 CE) | |||||

| Qunbul | 195 AH | 291 AH (904 CE) | ||||||||

| Abu 'Amr | 68 AH | 154 AH (770 CE) | Al-Duri | 150 AH | 246 AH (860 CE) | |||||

| Al-Susi | ? | 261 AH (874 CE) | ||||||||

| Ibn Amir ad-Dimashqi | 8 AH | 118 AH (736 CE) | Hisham | 153 AH | 245 AH (859 CE) | |||||

| Ibn Dhakwan | 173 AH | 242 AH (856 CE) | ||||||||

| Aasim ibn Abi al-Najud | ? | 127 AH (745 CE) | Shu'bah | 95 AH | 193 AH (809 CE) | |||||

| Hafs | 90 AH | 180 AH (796 CE) | ||||||||

| Hamzah az-Zaiyyat | 80 AH | 156 AH (773 CE) | Khalaf | 150 AH | 229 AH (844 CE) | |||||

| Khallad | ? | 220 AH (835 CE) | ||||||||

| Al-Kisa'i | 119 AH | 189 AH (804 CE) | Al-Layth | ? | 240 AH (854 CE) | |||||

| Al-Duri | 150 AH | 246 AH (860 CE) | ||||||||

| Abu Ja'far | ? | 130 AH | 'Isa Ibn Wardan | ? | 160 AH | |||||

| Ibn Jummaz | ? | 170 AH | ||||||||

| Ya'qub al-Yamani | 117 AH | 205 AH | Ruways | ? | 238 AH | |||||

| Rawh | ? | 234 AH | ||||||||

| Khalaf | 150 AH | 229 AH | Ishaq | ? | 286 AH | |||||

| Idris | 189 AH | 292 AH | ||||||||

Relationship between Qira'at and Ahruf

The legitimacy of variant oral readings is derived from some hadith narrations that the Qur'an was revealed to Muhammad in seven ahruf. The word ahruf literally means words or letters, but is commonly translated as modes of recitation. The nature of these ahruf generated a wide range of theories, some more plausible than others.[116] A popular, though problematic theory was that these were dialects of seven Arab tribes, and only one, that of the Quraysh was retained by Uthman. However, most variants among the canonical readings are not of a dialect nature[117]. It also makes little sense of Sahih Bukhari 9:93:640 in which Muhammad said the Quran was revealed in seven ahruf when two companions who were both of the Quraysh tribe disagreed on a reading. A more tenable view is that the ahruf represent variant readings at certain points in the Quran.

A related question on which scholars differed was whether or not all the ahruf were preserved. One group including Ibn Hazm (d.1064 CE) believed that all seven ahruf were accomodated by the Uthmanic rasm (consonantal skeleton), finding it unimaginable that anything would be omitted.[118]. Al-Tabari argued that only one harf was preserved by Uthman (which he interpreted to mean the dialect of the Quraysh), while Ibn al Jazari said the view of most scholars is that only as many of the ahruf as the Uthmanic rasm accommodated were preserved[119]. Indeed, this latter view is more viable theologically, for the non-Uthmanic companion readings must be fraudulent under the first view, and problems with the second view include those mentioned above.

As part of the majority view reported by Ibn al Jazari, the Uthmanic codex was based on the harf of the "final review" or final revealed version of the Quran[120]. However, there were around 40 scribal errors in the official copies of the Uthmanic text (see below).[121] Canonical qira'at were required to comply with this range rather than an entirely unified text. Indeed, in some cases they even strayed beyond these boundaries.[122]

Academic scholars who have analysed the isnads and matn of the transmissions generally believe that the main seven ahruf hadith (involving Umar) is very early. It is widely transmitted, with Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī (d. 124) as the common link.[123] It may have been invented at an early stage to accommodate the proliferation of variant readings. Given that the Qur'an and hadith reveal that Muhammad would forget entire verses, another plausible theory would be that he was inconsistent in his recitation and appealed to ahruf as a convenient excuse. In the most widely transmitted ahruf hadith, Muhammad explains the ahruf to pacify an angry Umar, who heard Hisham b. Hakim reading a surah in an unfamiliar way.[124] In another account, Ubayy b. Ka'b feels denial/disbelief (al takzeeb التَّكْذِيبِ[125]), the like of which he had not felt since before Islam, when Muhammad gives his approval to some unfamiliar and differing recitations (qira'at), then begs forgiveness when Muhammad explains the ahruf.[126] In another version, Muhammad's explanation to Ubayy gives significant leeway in how the Qur'an was to be recited.[127]

Differences in the Qira'at

Muslims are commonly told that the differences between the Qira'at can be explained away as styles of pronunciation or dialect and spelling rules. Called uṣūl, these are rules that apply to the entire reading, causing tens of thousands of tiny differences with no impact on meaning. Yet there is another category, called farsh, of individual differences that cannot be generalised in rules, which also includes changes in wording. In a few cases the variants added or omitted words, and others are completely different words or contradict each other in meaning. The Corpus Coranicum database[128], the Encyclopedia of the Readings of the Quran database[129], and the nquran website[130] can be used as neutral online sources for verifying the existence of such variations in the Qira'at. The Bridges translation of the Quran by Fadel Soliman can be selected on quran.com and highlights words with canonical variants, listing them in English with their readers as footnotes. An interesting example is given below, and more of them are listed in the tables in the next sections.

In Quran 18:86, Dhu'l Qarnayn finds the sun setting in a muddy spring, according to the Qira'at used by today's most popular transmissions of the Qur'an. However, in around half of the various Qira'at the sun intead sets in a warm spring. The latter variant is even used in some English translations. It is easy to see how the corruption arose (whichever one is the variant). The arabic word حَمِئَة (hami'atin - muddy) sounds very similar to the completely different word حَامِيَة (hamiyatin - warm). Al-Tabari records in his tafseer for this verse the differing opinions on whether the sun sets in muddy or warm water.

The reading of Ibn Amir, which is one of those qira'at containing hamiyah instead of hami'ah, is still used in some parts of Yemen, and used to be more widespread.[131]. In written form this difference is not just a matter of vowel marks. Even the consonantal text with dots is different, though in the original Uthmanic orthography they may have looked the same due to the very limited use consonantal dotting and word-internal ʾalifs (unwritten or inconsistent usage in most situations) at that time. A scan of a printed Qur'an containing the mushaf of Hisham's transmission from Ibn Amir's reading can even be read online and it can be seen that حَامِيَة (warm) is used in verse 18:86[132].

For further discussion, see the section Origin of the Qira'at Variants further below.

Differences in the Hafs and Warsh Texts

Apart from other earlier variant readings, and those of al-Duri from Abu Amr still used in Sudan, and of Hisham from Ibn Amir still used in parts of Yemen, there are two different readings of the Qur'an currently widespread in printed text (mushaf), named after their respective 2nd-century transmitters: Hafs from Asim (one of the Kufan readers) and Warsh from Nafi (of Medina).

The Hafs reading is the more common today and is used in most areas of the Islamic world, but this was not always the case. The popularity of Hafs arose during Ottoman times. Earlier, it was so unpopular that it is not found in manuscripts for the first several centuries (though was documented by Ibn Mujahid), and many of his variants that are unique among the canonical readers are attested in early manuscripts only as part of non-canonical secondary readings added later, if at all.[133] The Warsh reading is used mainly in West and North-West Africa as well as by the Zaydiya in Yemen. Here are some of the differences.

| Verse | Hafs | Warsh | Notes | Variants translation, transliteration, and Arabic script |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quran 2:125 | watakhizu (you shall take) | watakhazu (they have taken) | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com | |

| Quran 2:140 | taquluna (You say) | yaquluna (They say) | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com | |

| Quran 2:184 | miskeenin (poor person) | masakeena (poor people) | Instruction on how many people to feed to mitigate a broken fast | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 3:81 | ataytukum (I have given) | ataynakum (We have given) | These words are in a quote. They can't both be right. | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 3:146 | qatala (fought) | qutila (was killed) | The Warsh version better fits verse 3.144 | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 7:57 | bushra (good tidings) | nushra (disperse) | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com | |

| Quran 12:64 | khayrun hafithan (best guardian) | khayrun hifthan (best at guarding) | This is in a quote of Joseph's father. Why the variation? | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 19:19 | li-'ahaba (that I may bestow) | li-yahaba (that he may bestow) | This is in a quote of Gabriel's words to Mary. Which did he say?

The Sanaa 1 palimpsest gives a 3rd variant, li-nahaba, "that We may bestow"[122] In mushafs based on the Warsh transmission (and the reading of Abu Amr), unusual orthography is required due to the ya violating the Uthmanic rasm.[134] |

Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 21:4 | qaala (He said:) | qul (Say:) | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com | |

| Quran 30:22 | li-l-'aalimeena (for the knowledgable) | li-l-'aalameena (for the creations) | In all the other readings the things mentioned are signs li-l-ʿālamīna (for the creations) i.e. signs for all peoples as in Quran 21:91 and Quran 29:15, knowledgable or otherwise. | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 43:19 | 'ibaadu (slaves) | 'inda (with) | As with most of these examples, the rasm (early stage of Arabic orthography in use at the time of Uthman) is the same in both versions (عِندَ vs عِبَٰدُ), in this case allowing two completely different root words to be read since the rasm barely employed consonantal dotting and word-internal ʾalifs, and lacked short vowels at that time. | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 57:24 | Allaha huwa alghaniyyu (Allah, He, is self sufficient) | Allaha alghaniyyu (Allah is self sufficient) | This was also one of the regional Uthmanic rasm variants with no obvious value | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

Differences Between Other Canonical Readings

There are many more differences between other transmissions besides those of Hafs and Warsh. All are available in printed form and in the online sources mentioned above. The following are a few examples, mostly of conflicting variants in quoted dialogue incidents.

| Verse | Reading 1 | Reading 2 | Notes | Variants translation, transliteration, and Arabic script |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quran 5:6 | Ibn Kathir, Abu Amr,Shu'ba and Hamza read wa-'arjulikum (your feet [genitive case]) | The others read wa-'arjulakum (your feet [accusative case]) | The grammatical variance caused different rulings on wudu between Sunni and Shi'i (whether to rub or wash the feet)[135][136] | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 17:102 | al-Kisa'i reads 'alimtu (I have known) | The others read 'alimta (You have known) | Moses speaking to Pharoah | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 20:96 | Hamza and al-Kisa'i read lam tabsuroo (you did not percieve) | The others read lam yabsuroo (they did not percieve) | Samiri speaking to Moses | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 12:12 | The three Kufans (Asim, Hamza, and al-Kisa'i) read yarta' wa-yal'ab (he may eat well and play) | The others read narta' wa-nal'ab (we may eat well and play) | Joseph's brothers talking to their father | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 12:49 | Hamza and al-Kisa'i read ta'siroona (you will press) | The others read ya'siroona (they will press) | Joseph speaking to the King | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 12:63 | Hamza and al-Kisa'i read yaktal (he will be given measure) | The others read naktal (we will be given measure) | Joseph's brothers talking to their father | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 11:81 | Ibn Kathir and Abu Amr read 'illa mra'atuka (except your wife [nominative case]) | The others read 'illa mra'ataka (except your wife [accusative case]) | These variants give rise to conflicting instructions from the angels to Lot[137][138] | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 37:12 | Hamza and al-Kisa'i read 'ajibtu (I was amazed) | The others read 'ajibta (you were amazed) | Allah feels the emotion of amazement | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

The standard Islamic view is that every variant within the canonical qira'at (readings) were recited by Muhammad, and the canonical readers made choices from among the authentic variants passed down to them. The claim is that even when the variants are completely different words or when words are added or omitted, that these are all divinely revealed alternatives. Due to the constraint of a standard rasm and because any viable variant would need to make sense in context, most variants are mutually compatible. Yet critics point out that some examples such as in the tables above contradict each other. A viable explanation is also lacking for the large number of superfluous variants (examples of which are even more common - see the table in the next section).

It is also notable that the majority of consonantal dotting differences involve person or gender prefixes (t-, y-, n-), while a minority transform one root word into another, which seems to reflect the balance of ambiguity in the rasm. Function words are also often transformed into others by means of vowel and other diacritics, such as the few dozen cases of variants between inna (indeed), anna (that), or an (to).[139]

A more extensive study of differences between the Hafs and Warsh transmissions and comparisons with Qur'an manuscripts can be read online[140]. Further studies of dialogue variants and superfluous variants are also available.[141][142]

Redundant or superfluous variants

One of the most notable things about the canonical variants is that a large number do not convey any significant difference in meaning, or cause one or more of the other readings for a word to be redundant. Critics see this as a reason to doubt claims of a divine origin for such variants, which instead are typical of human oral performance variety or transmission errors. A few illustrative examples of major categories of such variants are given in the table below, which in most cases could be read from the same rasm, differing only when consonantal dotting or vowel diacritics were added.

| Verse | Reading 1 | Reading 2 | Notes | Variants translation, transliteration, and Arabic script |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quran 2:116 | Ibn 'Amir read qalu "They say" | The others read wa qalu "And they say" | This is an example of a regional rasm variant which has no significant value. | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 19:25 | Ya'qub reads "It will drop" yassāqaṭ where "it" refers to the (masculine) trunk | The others read "It will drop" tusāqiṭ (form III), tassāqaṭ (form VI) or tasāqaṭ (assimilation) where "it" refers to the (feminine) palm tree | An example with a high number of variants, suggesting much uncertainty about the word. A total of four canonical variants are listed in the Corpus Corunicum link. It further documents several non-canonical variants for this same word such as nusqiṭ (we will cause to drop, as in Quran 34:9). See also the discussion of this verse in Lane's Lexicon p.1379) | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 21:96 | Ibn 'Amir, Abu Ja'far and Ya'qub read futtihat "opened wide" (more intensive form) | The others read futihat "opened" | An example where the more intensive form II renders the majority form I reading redundant. If a gate is opened wide, that already implies it is opened, so there is no purpose in the latter variant. | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 23:115 | Ya'qub and the related Kufan readings of Hamza, Kisa'i and Khalaf read tarji'una "return" | The others read turja'una "be returned" | An example of active-passive variants. These are very common, involving vowel differences. The passive "be returned" in this case makes the active redundant as it is already implied. | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

| Quran 59:14 | Ibn Kathir and Abu Amr read jidarin "a wall" (singular) | The others read judurin "walls" (plural) | An example of singular-plural variants where there is no discernable purpose in having both | Bridges translation Corpus Coranicum nquran.com |

The number of Qira'at variants, canonical and non-canonical

Altogether, there are around 1,400 words with variants among the canonical readings of the Quran[143][144], about two percent of the total. These are the farsh differences mentioned above. Some are regarded as dialect differences, while others including vowel differences affect grammar and meaning. Around 300 involve different consonantal dotting, generally changing attached pronouns or sometimes producing a different root word. In addition, there are around 40 variants arising from the regional Uthmanic codices (see below), in a few cases adding or omitting insignificant words. It is common for a word to have more than two variants, with no obvious intention in so much variety.[145]

Beyond the canonical variants, the numbers become truely vast. In 2002, Abd al-Latif al-Kitab published his authoritative compendium of qira'at variants, Mu'jam al-Qira'at, which is commonly cited by academic scholars. The main ten volumes list variants reportedly read by the canonical readers and transmitters, the companions, and other early reciters, mostly of the first two centuries.[146] Together, these come to approximately 6,000 pages with around 5 variants listed per page. In 1937, Arthur Jeffery had compiled over 2000 companion variants in a smaller work.[7] The bulk of al-Khatib's compilation thus comprises the variants reportedly read by other early reciters, for example al-Hasan al-Basri or his students. These non-canonical variants include both those that comply with and those that do not fit the Uthmanic rasm standard. It is inconceivable that anywhere near this number of variants for the same words could have been part of Muhammad's recitation. Most of them must post-date the standardisation.

In terms of the material evidence, virtually all known manuscripts are of the Uthmanic text type, the oldest of which lack diacritics and therefore limits the ability to identify variants. Early vocalised manuscripts with diacritics tend to mainly involve canonical variants (albeit the reading as a whole is rarely recognisable as belonging to any known reader). However, as noted above, the Sanaa 1 palimpsest is known for having dozens of non-Uthmanic variants similar to those reported of the companions. In addition, a PhD thesis by leading Quranic manuscript expert, Alba Fedeli, describes a few of the very early Mingana collection manuscripts (including the famous Birmingham fragment, which is now known to be actually part of a larger manuscript). This was notable in that most of the recognisable qira'at variants therein complied with the Uthmanic rasm standard, but were mostly not canonical, matching instead variants reported of companions or (more commonly) early non-canonical reciters.[147]

Implications of these numbers

Critics argue that it is hard to explain why there would be so many authentic variants available that just so happened to be accommodated by the Uthmanic orthography or sound similar, even granting the rasm selection effect. Van Putten has made a similar point.[148] As mentioned above, around 1,400 out of c.77,000 words in the Qur'an have canonical variants. There are two further considerations which greatly multiply the scale of the problem: 1) There is no reason to assume that even if genuine, these were the only variants that Muhammad uttered which complied with the (yet to be standardised) rasm. 2) There is no reason to assume that he would only have uttered variants that would later fit the Uthmanic rasm standard. Indeed, the companion variants often do not fit this standard. Therefore, the variants would just be a small subset of those he really uttered before any rasm constraint. If the canonical variants are all authentic, these considerations would therefore imply many thousands more. It is far more likely that most of the canonical variants post-date the rasm standard.

Further, it seems doubtful that the Uthmanic rasm standardisation would have been successful had it required so many words to be discarded by the early Muslim communities. A large number of variants would also have provided ample cover for inauthentic ones to be innovated, deliberately or otherwise. The companions would not have had perfect memories, and where we do have reports of companions reading particular canonical variants, sometimes they were attested only of a single companion such as Ibn Mas'ud, or 'Ali when he disliked the main reading.[149]

Origin of the Qira'at Variants

The Uthmanic codex was written in a rasm, which is a "defective" Arabic script, meaning that it lacked most word-internal ʾalifs (unwritten or inconsistent usage in most situations), had no markings for short vowels, and sparse (if any) dots that were in later times used to distinguish the many different but identically written consonantal letters.

Professor Shady Nasser shows that at the time when Ibn Mujahid wrote his Kitab al Sab'ah selecting the 7 eponymous readings that later became canonical, adherence of readings to the Uthmanic rasm and good Arabic grammar were already important criteria [150], but Ibn Mujahid restricted his selection to just 7 by choosing the consensus readings from each of Mecca, Medina, Basra, Syria and the 3 most popular readers from Kufah, where the legacy of Ibn Mas'ud's (now banned) reading meant that there was no dominant Uthmanic reading in that city.[151]. Ibn Mujahid's decision to select just 7 readings drew frequent criticism after its publication[152].

Dr Marijn Van Putten has shown that while the canonical readings largely comply with the Uthmanic rasm, more specifically they also each closely comply with the regional variants of that rasm, which were sent out to the major intellectual centres of early Islam and contained a small number of copying mistakes. So, the Kufan readings closely correspond to the variants found in the rasm of the codex given to that city and so on.[153][154]

This would be an extraordinary coincidence if the variants are entirely due to oral transmissions going back to the recitations of Muhammad (though certainly the general agreement between readings where the rasm is ambiguous demonstrates that there was also oral transmission [155]). Instead, the regional correspondence of rasm and oral reading variants is easily explained if the readings were adapted to fit the codices given to those regions. By analysing the reported variants between regional codices, modern scholarship has confirmed that they form a stemma (textual tree relationship), suggesting that those particular variants did not originate in oral transmission.[156] Van Putten sets out these and other arguments that the readings depend not just on oral transmission but also to an extent on the rasm in his open access book Quran Arabic: From its Hijazi origins to its classical reading traditions.[157]

If qira'at variants could sometimes arise from variants in the rasm, we should also expect this to occur even in places where the rasm did not vary. Munther Younes highlights a particularly interesting example among the hundreds known.[158] In Quran 4:94 we have the canonical variants fa-tabayyanū or fa-tathabbatū. In this case, the variant root words do not share even a single consonant in common (bāʼ-yāʼ-nūn versus thāʼ-bāʼ-tāʼ), but nevertheless both variants fit the defective script of the Uthmanic rasm, which lacked dots and vowels. Other examples of variants with the same rasm include Quran 6:57, where 4 of the canonical 7 qira'at have yaqḍi l-ḥaqqa "He judges the truth" rather than yaquṣṣu l-ḥaqqa "He declares the truth"[159] and Quran 10:30 where two readers have tatlū (recounts, recites), whereas the other five have tablū (tests) [160]. In these examples the similarity between the variant readings is graphic (how the rasm looks) rather than phonic (how they sound) and involve consonantal dotting differences that transform one word into another, though short vowel differences make up the bulk of variants.

The seven eponymous readings are only rarely evident in the earliest manuscripts. The vast majority of vocalised manuscripts contain unknown or non-canonical reading systems. They contain the above mentioned regional differences, but also sometimes reflect dotting and lettering traceable to the more substantial variant readings of the Companions and not necessarily of the seven.[60]

Criticism of variant readings which were later treated as infallible

Nasser has shown that grammarians such as al-Farra[161], and scholars such as al-Tabari readily criticised variants in these same readings shortly before they were canonized[162] (as did al-Zamakhshari 200 years afterwards)[163]). Even Ibn Mujahid said some variants now considered canonical were wrong.[164] It was even more common for early scholars to argue their preference for particular variants. After Ibn Mujahid's book, a genre of literature arose that "indicates the rising need to provide grammatical and syntactic proofs in order to back up the arguments necessary to assess the superiority of one reading over another." [165]. The consensus notion that all variants in these 7 were divinely preserved in a chain back to the Prophet himself only came about later, by which time there was of course no room for arguments and reasoning to try to prove the superiority of one variant over another.[166] As Nasser writes, "The problem that caused heated discussion for centuries afterwards was the origin and transmission of the eponymous Readings; were these Readings transmitted through tawātur or single chains of transmission? Are there Readings better than others or are they equally divine?"[167].

Controversy over mutawatir (mass transmitted) status

The majority of the Qur'an where there was full agreement between readers was considered to have been orally mass transmitted from the beginning to such an extent that there could be no doubt about it. However, the transmission status of the disagreements between the readings was more controversial. While the readings were indeed widely transmitted (with more variants along the way) from the eponymous readers to their students and so on, the transmission of the variants from Muhammad to the eponymous readers was in question. As mentioned in a section above, even Ibn al-Jazari eventually decided that these did not meet mutawatir status.

While Ibn Mujahid only gave formal isnads from himself back to the Eponymous readers (whose readings he documented partially based on written notes[168]), he gave some biographical sketches of the small number of single chain transmissions between the Prophet and these readers, which generally had at least 4 or 5 links though occasionally 3.[169] Most of the seven main readers and their canonical transmitters did not escape criticism for their reliability in hadith and/or their Qur'an recitations in at least some biographical sources[170].

Challenges of the Qurra' Community

In a detailed monograph on Ibn Mujahid's canonization of the seven readings, Nasser shows that written notes played a significant role in transmission of the readings in the 2nd century. Despite their best efforts, some canonical readers and their transmitters were said to have doubts about their (often unique) reading variants. Abu 'Amr, al Kisa'i, Nafi, and the transmitters of 'Asim (Hafs and Shu'ba) are all reported "retracting a reading and adopting a new one" in some cases. Shu'ba "became skeptical" of his teacher 'Asim's reading of a certain word and adopted another, and said he "did not memorize" how certain words were read. In one instance Ibn Dhakwan, the transmitter of Ibn Amir's reading, found one reading for a word in his book/notebook, and recalled something different in his memory. When the detailed recitation of a word was unknown, "the Qurrāʾ resorted to qiyās (analogy)", as too did Ibn Mujahid when documenting the readings as he often faced conflicting or missing information. There were also cases of transmitters misattributing variants to the wrong eponymous reader (some transmitted more than one reading), and readers adapting to what they regarded as flawed parts of the Uthmanic rasm.[171]

In one summary he writes, "The multiple readings reported on behalf of the same Eponymous Reader or Canonical Rāwī, were not only due to transmission errors, inaccuracies, the 'flexibility' of the consonantal rasm, and the existance of a depository of different, yet acceptable traditions from the previous generations of Qurʾān masters. These readings were also generated because Qurʾān Readers occasionally modified and changed their readings over time, retracted certain readings, corrected others, and struggled to remember how precisely some variants were performed."[172]

Changes to the spoken Arabic dialect of the Qur'an

In a number of papers and a book dedicated to the topic (all open access in pdf format),[173] van Putten has identified that the Quranic Consonantal Text (QCT) reveals certain features about the Hijazi dialect in which it was originally uttered. These do not match the dialects found in the canonical qira'at, nor for this reason the orthography of Qur'ans published today. Evidence from internal rhyme is particularly helpful in this regard (the traditional qira'at recitations and later orthography sometimes break the rhyming structure of a passage), supplemented by ancient epigraphic (inscription) evidence, including transliterations of the Arabic of that region and time into other languages. Van Putten and Stokes have found that the QCT "possessed a functional but reduced case system, in which cases marked by long vowels were retained, whereas those marked by short vowels were mostly lost".[174] Van Putten has also found, in line with the accounts of early Muslim linguists, that the Hijazi dialect spoken by Muhammad had lost the use of the hamza except for word-final ā.[175] He has also found that nunation at the end of feminine nouns ending with -at was not present in this dialect.[176]

These findings are summarised in chapter 7 of van Putten's book published in 2022 Quranic Arabic: From its Hijazi origins to its classical reading traditions (downloadable free in pdf format)[173] [177] In the book he further marshals many additional lines of evidence, all supporting that the QCT was composed in Hijazi Arabic and that it lacked ʾIʿrab (grammatical case vowel endings) as well as tanwin present in "classical" Arabic and the canonical readings. Pragmatic considerations and extra-linguistic hints would have resolved to a large extent the resulting ambiguities. Nevertheless, "to the Quranic reciters, placement of ʔiʕrāb and tanwīn was a highly theoretical undertaking, not one that unambiguously stemmed from its prototypical recitation and composition."[178] Chapter 8 usefully puts the findings of the book in the context of the historical development of the reading traditions.

Reports about Al Hajjaj and the Uthmanic Qur'an

Al-Hajjaj Ibn Yusuf Al-Thakafi, who lived in the years AD 660-714, was a teacher of the Arabic language in the city of Taif. Then he joined the military and became the most powerful person during the reign of Caliph Abd al-Malik Ibn Marawan and after him his son al-Waleed Ibn Abd al-Malik.

One report in Ibn Abi Dawud's Kitab al-Masahif claims that the Uthmanic Qur'an was changed by Al-Hajjaj, inserting 11 small changes into the text and sending them out to the main cities. However, this report is not considered credible by academic scholars for a number of reasons, including the fact that all extant manuscripts (except for the Ṣan'ā' 1 palimpsest lower text) can be traced to a single archetype, as explained above. Moreover, Sadeghi and Bergmann have shown that the Basran author of this report about al-Hajjaj had simply mistaken some errors in a particular manuscript as being the Uthmanic standard and compared it with the manuscript of al-Hajjaj.[179]

Adam Bursi has noted that a number of accounts exist that al-Hajjaj sought to reduce the proliferation of erroneous readings of the Qur'an, though the details of such accounts are challenged by material manuscript evidence. Dotting marks to distinguish homographic consonants were already used sparingly before Islam, which causes Bursi to agree with Alan Jones that "the most that al-Ḥajjāj could have insisted upon was the revival and regular use of earlier features already available within the Arabic script." Further details about the members of a committee of Basran experts formed by al-Hajjaj seem dubious, appearing only in later reports. During the governorship of al-Hajjaj, there is "no evidence of the imposition of the kind of fully dotted scriptio plena that the historical sources suggest was al-Ḥajjāj’s intended goal. There is some manuscript evidence for the introduction of short vowel markers into the Qurʾān in this period, but this development is not associated with the introduction of diacritics as our literary sources suggest." [i.e. they wrongly suggest both consonantal and vowel marks were introduced at the same time] Bursi concludes that "While ʿAbd al-Malik and/or al-Ḥajjāj do appear to have played a role in the evolution of the qurʾānic text, the initial introduction of diacritics into the text was not part of this process and it is unclear what development in the usage of diacritics took place at their instigation."[180]

Similar to Bursi, Nicolai Sinai is skeptical of detailed reports about the contribution of al-Hajjaj, and of Omar Hamdan's acceptance of reports that al-Hajjaj replaced existing mushafs with his own version (the so-called "second masahif project"), though Sinai does find more convincing the reports that al-Hijjaj sought to enforce the Uthmanic rasm standard under the Caliphate of 'Abu al-Malik b. Marwan and, particularly, to suppress the continued use of the non-Uthmanic reading of Ibn Mas'ud in Kufa.[181]

See also

- Quran Variants - Articles and Resources page

References

- ↑ The Naqad Islamic Studies server is described as an open resource server for print and online collections that support Late Antique, Near Eastern and Islamic Studies. They write, "This diagram aims to represent the most rigorous academic insights on the topic, and is a collaboration between our contributors and the top Quranic linguists and epigraphers in the field of Quranic studies." Naqad Islamic Studies - Twitter.com

- ↑ "We have, without doubt, sent down the Message; and We will assuredly guard it (from corruption)." - Quran 15:9