Cousin Marriage in Islamic Law

This article or section is being renovated. Lead = 2 / 4

Structure = 4 / 4

Content = 3 / 4

Language = 4 / 4

References = 4 / 4

|

Cousin marriages, including those between first cousins, are permitted by Islamic law and scriptures and were practiced by Muhammad himself as well as his companions. Muhammad's practice of cousin marriage, in addition to cementing the legality of the practice, renders the practice a sunnah, or a good deed worthy of commendation, given Muhammad's status as al-insan al-kamal (lit. 'the perfect man'). Cousin marriages have been the common throughout Islamic history[1] and remain so in Muslim-majority nations today, comprising a significant percentage of the total population of these nations.

Children born of cousin marriages face an increased risk of genetic disorders and childhood mortality[2][3] and are thus prohibited in some countries.[4][5] One study estimated infant mortality at 12.7 percent for married double first cousins, 7.9 percent for first cousins, 9.2 percent for first cousins once removed/double second cousins, 6.9 percent for second cousins, and 5.1 percent among non-consanguineous progeny. Among double first cousin progeny, 41.2 percent of pre-reproductive deaths were associated with the expression of detrimental recessive genes, with equivalent values of 26.0, 14.9, and 8.1 percent for first cousins, first cousins once removed/double second cousins, and second cousins respectively.

There is an increasing awareness in the Muslim world of the risks of multi-generational cousin marriage, and an increasing number of voices calling for it to be discouraged (even if it remains permitted).

Cousin marriage in scripture

Quran

Quran 4:23, in leaving out mention of one's cousins in its list of those relatives to whom marriage is prohibited, permits cousin marriage.

Quran 33:50, in discussing the exclusive marital rights of the prophet Muhammad, explicitly permits him to marry his first cousins.

Hadith and sirah

Muhammad

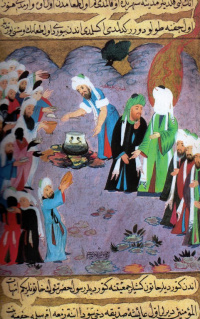

Muhammad married his cousin Zaynab bint Jahsh who, in addition to being the daughter of Umaimah bint Abd al-Muttalib (a sister of Muhammad's father), was also the former wife of his adopted son, Zayd ibn Harith. The marriage proved immensely controversial - not because Zaynab and Muhammad were cousins (cousin marriages being fairly common throughout much of the ancient world), but because Zaynab had been previously been married to Muhammad's adopted son. The controversy was of such scale that Muhammad ultimately produced revelation in the Quran addressing the matter, absolving him of any proposed guilt.

According to Ibn Sa'd, after Zaynab's marriage to Zayd, Muhammad went to visit him, but instead encountered a hastily clad Zaynab. Though he did not enter the house, the sight of her pleased him. Tabari states that Zaynab was only wearing a single slip and that the wind pushed away a curtain when Muhammad entered, revealing her 'uncovered'. Thereafter, Zayd no longer found her attractive and thought of proposing divorce, but Muhammad told him to keep her. Eventually, however, Zayd did divorce her. After this, Muhammad and Zaynab were wed.[6]

Ali

In addition to marrying a first cousin himself, Muhammad also allowed the marriage of his daughter, Fatimah, to his first cousin, Ali ibn Abi Talib, who would later become the fourth Rightly-Guided Caliph of Islam.

Umar

The second Rightly-Guided Caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab, also married his cousin, Atikah bint Zayd ibn Amr ibn Nufayl.[7][8]

In the Islamic world today

The British geneticist, Professor Steve Jones, giving The John Maddox Lecture at the 2011 Hay Festival had stated in relation to inbreeding in the Islamic world, "It is common in the Islamic world to marry your brother’s daughter, which is actually [genetically] closer than marrying your cousin."[9]

Pakistan

Cousin marriage has been common in Pakistan for generations. According to professor Anne-Marie Nybo Andersen from South Danish University, the current rate is about 70%.[10]

Pakistani emigrants

A BBC report on Pakistanis in the United Kingdom finds that 55% of them marry a first cousin. Many of the children of such consanguine marriages themselves marry cousins. The report states that these children born from repeated generations of first-cousin marriages are 13 times more likely than the general population to suffer from genetic disorders. Nearly one in ten of the children born of these marriages in Birmingham either dies in infancy or develops a serious disability. The BBC report also states that Pakistani-Britons, who account for some 3% of all births in the UK, produce "just under a third" of all British children with genetic illnesses.[11]

Multiple scientific studies show that the mean (average) perinatal mortality in the Pakistani community of 15.7 per thousand significantly exceeds that of the indigenous population and all other ethnic groups in Britain. Congenital anomalies also account for 41 percent of all British Pakistani infant deaths.[12][13][14][15]

Turkey

In Turkey the percentage of total marriages that are contracted between cousins is between 25-30 percent.[16]

Arab nations

Statistical research on Arab countries shows that up to 34% of all marriages in Algiers are consanguine (blood related), 46% in Bahrain, 33% in Egypt, 80% in Nubia (southern Egypt), 60% in Iraq, 64% in Jordan, 64% in Kuwait, 42% in Lebanon, 48% in Libya, 47% in Mauritania, 54% in Qatar, 67% in Saudi Arabia, 63% in Sudan, 40% in Syria, 39% in Tunisia, 54% in the United Arabic Emirates and 45% in Yemen.[17][18]

See Also

External Links

References

- ↑ Goody, Marriage and the Family in Europe

- ↑ Bittles, Alan H.; et al. (10 May 1991). "Reproductive Behavior and Health in Consanguineous Marriages". Science. 252 (5007): 789–794. doi:10.1126/science.2028254. PMID 2028254, p. 790

- ↑ Bittles, A.H. (May 2001). "A Background Background Summary of Consaguineous marriage" (PDF). consang.net consang.net. Retrieved 19 January 2010. citing Bittles, A.H.; Neel, J.V. (1994). "The costs of human inbreeding and their implications for variation at the DNA level". Nature Genetics. 8 (2): 117–121

- ↑ "The Surprising Truth About Cousins and Marriage". 14 February 2014.

- ↑ Paul, Diane B.; Spencer, Hamish G. (23 December 2008). ""It's Ok, We're Not Cousins by Blood": The Cousin Marriage Controversy in Historical Perspective". PLOS Biology. 6 (12): 2627–30. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060320. PMC 2605922. PMID 19108607.

- ↑ Bewley/Saad 8:72; Al-Tabari, Vol. 8, p. 4; Al-Tabari, Vol. 39, p. 180; cf. Guillaume/Ishaq 3; Maududi (1967), Tafhimul Quran, "Al Ahzab"

- ↑ History of the Prophets and Kings 4/ 199 by Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari

- ↑ al-Bidayah wa al-Nihayah 6/352 by ibn Kathir

- ↑ Jonathan Wynne-Jones - Hay Festival 2011: Professor risks political storm over Muslim 'inbreeding’ - The Telegraph, May 29, 2011

- ↑ Flere dødfødsler blandt indvandrere (Danish language) - fpn.dk,February 27, 2009

- ↑ Justin Rowlatt - The risks of cousin marriage – BBC News, November 15, 2005

- ↑ Alan H. Bittles - The Role and Significance of Consanguinity as a Demographic Variable - JSTOR

- ↑ Polygamist community faces genetic disorder – China Daily, June 15, 2007

- ↑ John Dougherty - Forbidden Fruit – Phoenix New Times, December 29, 2005

- ↑ A. H. Bittles and M. L. Black - Consanguinity, human evolution, and complex diseases – PNAS, June 25, 2009

- ↑ More stillbirths among immigrants - Jyllands-Posten, February 27, 2009

- ↑ Consanguinity and reproductive health among Arabs - Tadmouri et al. Reproductive Health 2009 6:17

- ↑ Muslim Inbreeding: Impacts on intelligence, sanity, health and society - Nicolai Sennels - EuropeNews, August 9, 2010